Anatomy of a decacorn: tech vs. biotech

Richard Murphey

In this post, I will examine the returns generated by venture investments in some of the largest tech and biotech startups of the last few years.

Although biopharma is the second largest sector in venture capital after software, until recently, the tech and biotech startup worlds have been largely independent. Biopharma was thought to be too risky, too regulated, and too capital intensive to be an attractive sector for generalist investors.

But in the last few years, biopharma VC has outperformed tech, led by a new generation of high-growth biotech companies. How do these biotech unicorns compare to their tech counterparts? And how might these differences influence investment strategies?

The companies

This analysis focuses on the biggest tech and biotech startups of recent years. You’ve probably used products made by all of the tech companies on the list: Snap, Twitter, Pinterest, Dropbox, Uber, Lyft and Zoom.

But unless you work in biotech, you’ve probably never heard of any of these biotech companies.

From what I can tell, these are the best-returning biotech investments of the last 5 years. They are all therapeutics companies. I’m not sure if these tech investments are also the best-returning, as I’m more familiar with biotech than tech, but these were some of the biggest tech startups I know of that went public recently (and thus have published the prices of their venture rounds).

These companies are clearly outliers. But venture capital (especially in tech) is a game of outliers, not averages. The “power law” theory of venture capital – that one investment in a company like Uber can make up for hundreds of failed investments – governs the investment strategy of most tech VCs. While in most fields studying outliers does not yield many generalizable findings, studying outliers in VC is a helpful exercise.

Returns and portfolio theory

Understanding this post requires a bit of context and some very simple math. If you are familiar with how venture capital works and how investors measure financial returns, you can skip this section.

In this post, when I say “returns” I refer to cash-on-cash returns, also known as multiple-on-invested-capital (MOIC). MOIC is a simple metric: it represents the proceeds an investor receives from an investment divided by the amount invested in a company.

MOIC = value of investment / dollars invested

If a venture fund invests $10M into a company, and in five years that investment is worth $100M, the MOIC for the investment is 10x.

The concept of MOIC for an investment in a VC fund is very similar to the concept of MOIC for an investment in a startup: the MOIC of a fund is the proceeds from all investments divided by the total amount invested.

As a rule of thumb, most VCs try to get at least a 3x return on their fund. So a $300M fund wants to turn that $300M into at least $900M.

There are many ways that a $300M fund could generate $900M from its investments. For example:

- It can invest $300M into one company that triples in value.

- It can invest $10M into 30 companies. If half of those companies fail, 10 return 2x the amount invested (so they return $20M each * 10 companies = $200M), and the remaining 5 return 15x (15 * 10 * $10M = $750M), then the fund will be a ~3x ($950M in proceeds / $300M invested).

- According to the power law theory of startup investing, most funds plan on investing, for example, $10M into 30 companies each, and hope that a few generate 50x. Two 50x investments would generate proceeds of $1,000M. Even if the other 90% of the fund’s investments go to zero, the fund is still successful.

An important corollary of the power law is that, because 5-10% of startup investments account for the majority of all VC returns, the only thing that matters for investors is to invest in those 5-10% of outlier startups. It doesn’t matter if all of their other investments fail, or if they invest at high valuations, because the Ubers and Twitters of the world generate such high returns that they make up for everything else.

But that’s theory. What do actual returns from recent outlier companies look like?

Actual returns in tech and biotech

Below are the estimated cash-on-cash returns for seed, Series A and Series B investments in these startups 1. These returns represent valuations at December 31, 2019 for public companies that have not been acquired, or valuation at acquisition for those that have been acquired.

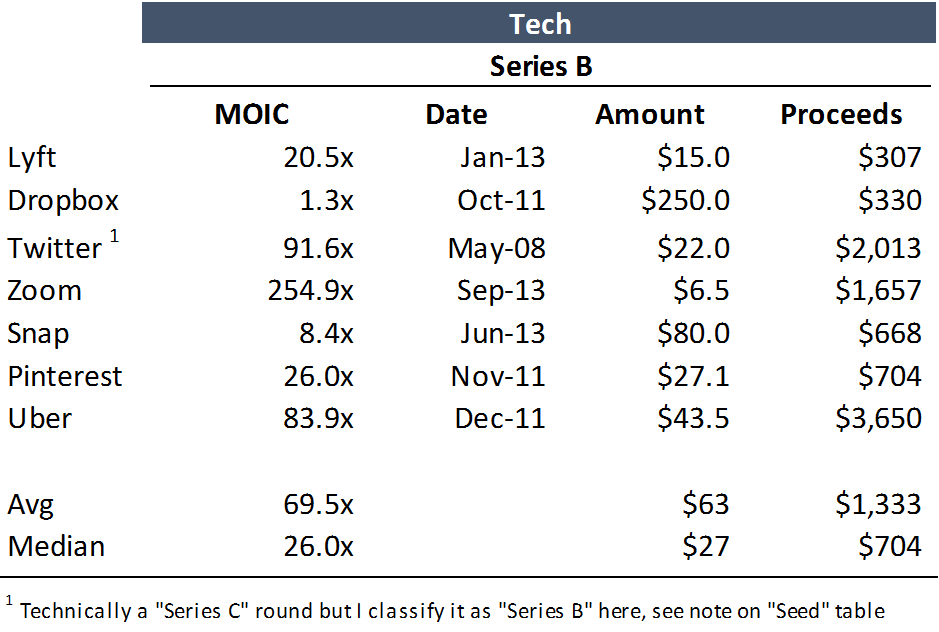

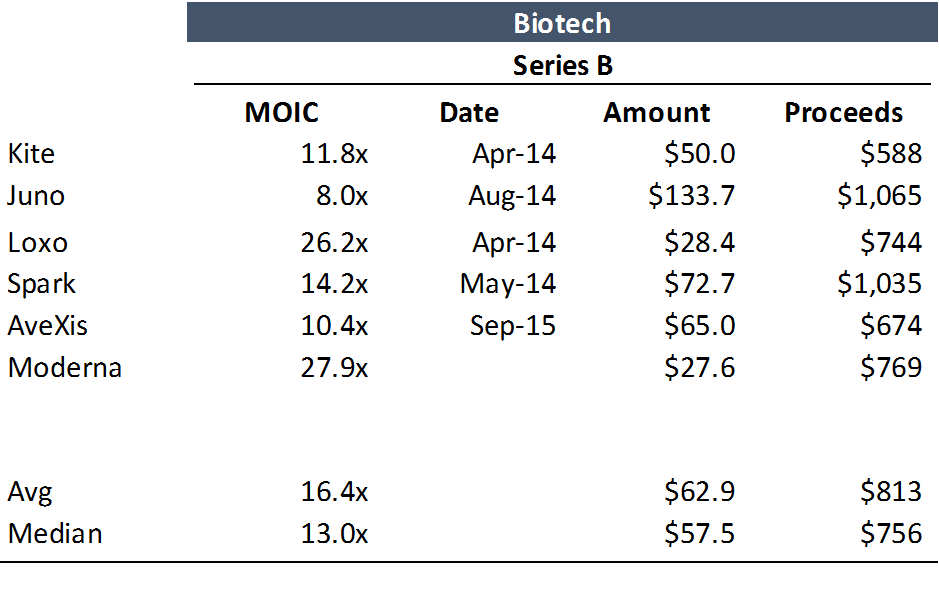

Series B returns

All of these investments generated amazing returns. But tech did a bit better: Series B investments in tech startups generated higher cash-on-cash returns than Series B investments in their biotech counterparts.

However, these Series B investments in tech and biotech startups generated comparable proceeds on an absolute basis. The Series B rounds in biotech startups were larger on average than tech Series B deals, which compensated for the lower cash-on-cash returns.

In other words, a Series B investment in a top biotech startup generates roughly the same proceeds as a Series B investment in the most successful tech startups. If you led the Series B in Juno, investing 25% of the total $134M raised, you would have received $270M when the company was acquired. If you invested 25% of Pinterest’s Series B, your investment would only be worth $176M at IPO valuation.

But because the biotech rounds are larger, a biotech fund of a given size cannot make as many investments as a tech fund of the same size. Based on the median Series B round sizes above, a $300M Series B-focused biotech fund could afford to make 20 investments. A $300M tech fund could make 45 investments – more than double the number of investments the biotech fund could make.

Thus tech investors can afford to make more losing investments than biotech investors.

It's important to remember that we are looking at returns from the most successful investments of the last few years. Most funds won’t be able to make investments that are this successful. So they will need to be even smarter about picking the right investments.

But this analysis is just for Series B investments. What about earlier stage deals?

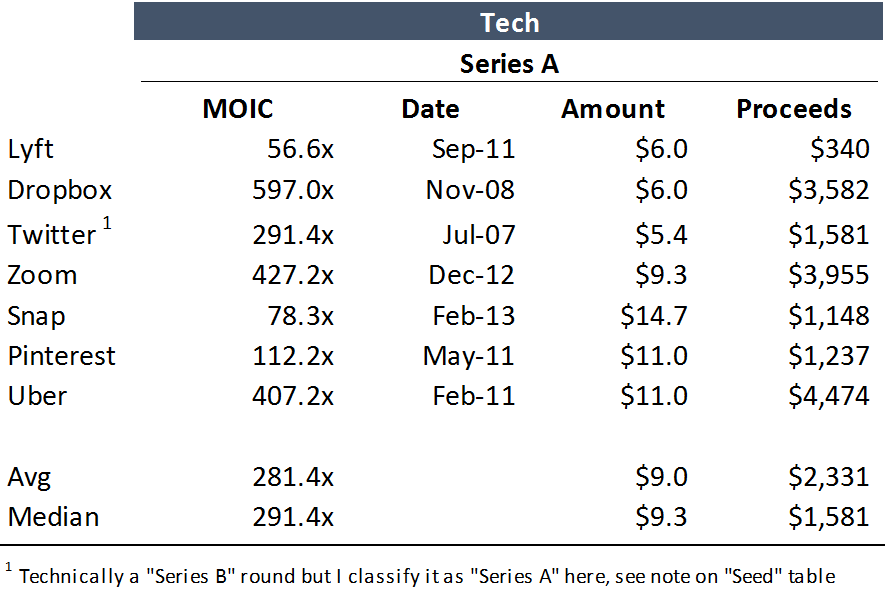

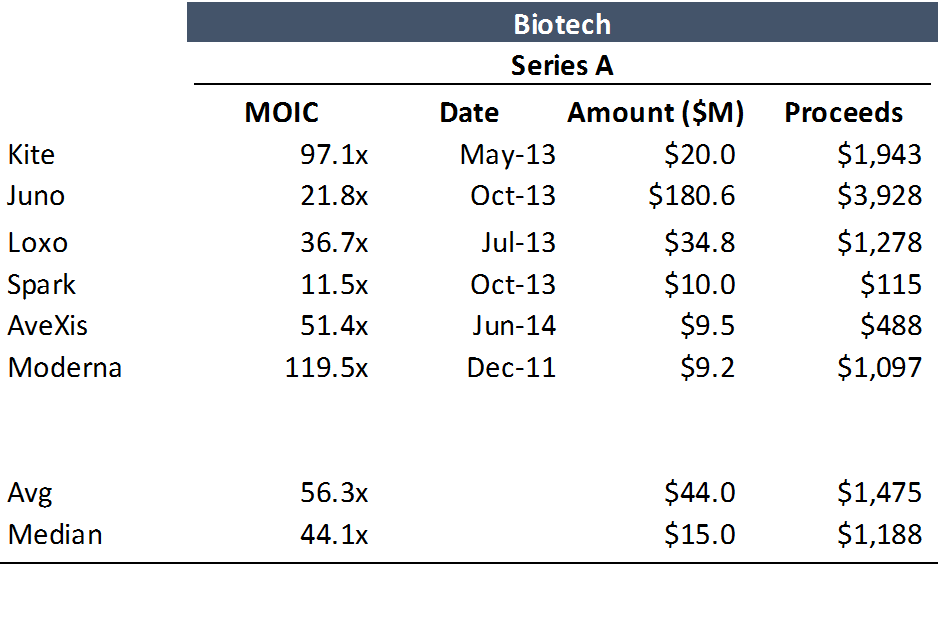

Series A returns

As we would expect for earlier-stage investments in riskier companies, the returns are much higher. The cash-on-cash returns in tech are higher than biotech, but the biotech returns are strong.

Also expectedly, the amounts invested are smaller than for Series B investments. And again, biotech rounds are larger than tech rounds.

The difference between overall proceeds in tech vs. biotech is smaller than the difference in cash-on-cash returns. The lower cash-on-cash returns in biotech are somewhat offset by larger round sizes. Just as in Series B investing, biotech funds can generate similar proceeds per investment as the most successful tech investments. Juno's Series A investors generated more proceeds on an absolute basis than Series A investments in any of these tech companies apart from Uber. But biotech funds can’t afford to make as many bets, so they need to have more conviction in the bets they do take.

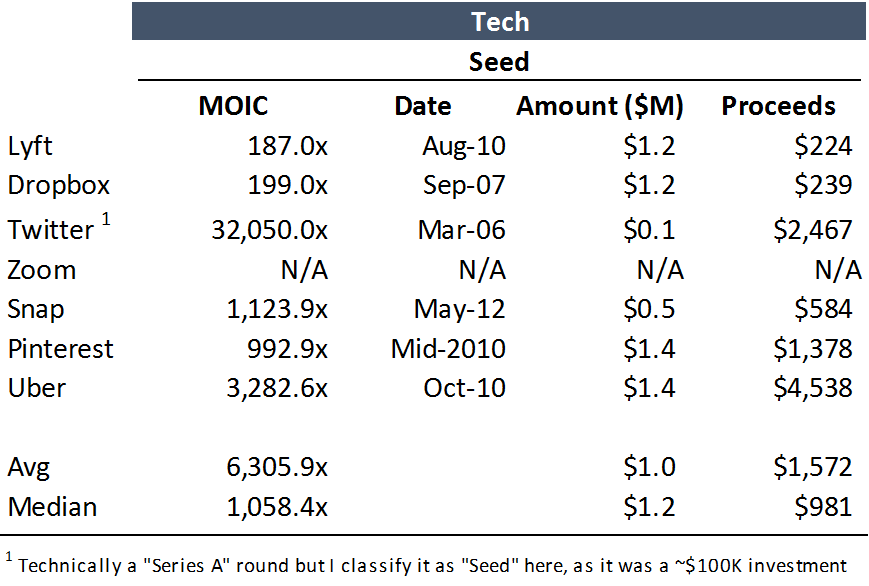

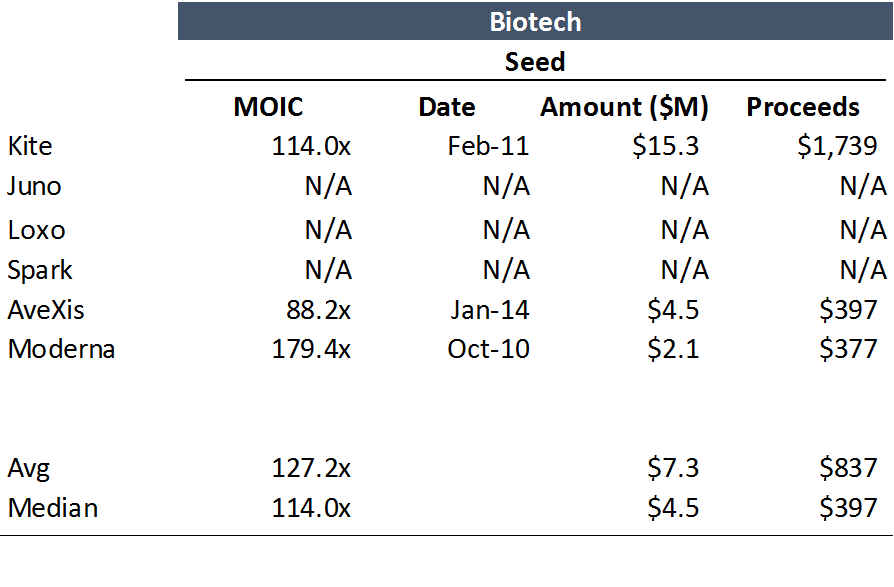

Finally, we will look at returns to seed investments. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find data on seed valuations and returns for half of the biotech deals, but we’ll take a look anyway.

Seed returns

It seems to be the same story with seed investing as with Series A and B investing: larger rounds and lower returns in biotech, but similar potential for absolute proceeds. However, tech seed investments appear to have a higher return “ceiling” than biotech seed investments. These tech investments had cash-on-cash returns that were an order of magnitude or more higher than the biotech seed MOICs. The delta between tech and biotech MOICs was not nearly as large for Series A and B deals as it was for seed deals.

Defensible clinical trial cost estimates

Get transparent cost estimates for any trial in minutes. Input an NCT ID or upload a protocol, then see a full cost analysis report.

Why are outlier returns lower in biotech?

Until a few years ago, the most common view among generalist VCs and angels was that biotech startups aren’t good investments because they don’t grow as big as software companies, they grow more slowly, and they are too capital intensive. This was true 10-15 years ago, when the biotech world was very different.

But, at least for this subset of very large companies (and for the sector at large, though that’s a subject for another post), these are misconceptions.

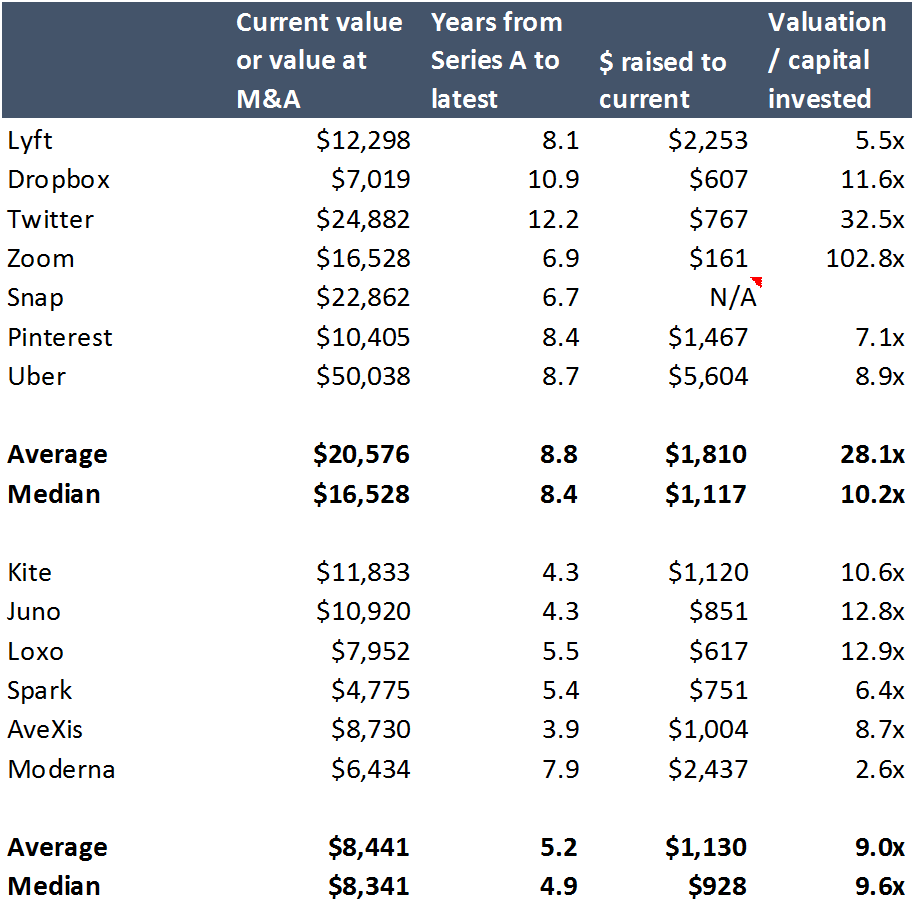

Overall, the biggest tech companies grew to be about twice as large as the biggest biotech companies. However, these tech companies are older, and it isn't fair to compare the valuation of a tech company nine years after Series A to a biotech company five years after Series A. The biotech companies grew to $8-9B valuations in five years from Series A, while the tech companies grew to valuations of $15-20B in 9 years.

And the tech companies required more capital to grow to this size than their biotech counterparts. Although again, the tech companies raised this capital over 9 years on average, versus 5 years for biotech companies. One measure of capital efficiency is valuation / dollars invested. The median valuation / dollar invested in tech and biotech is about the same, although the average valuation / dollar invested is much higher in these tech companies.

So these tech companies appear to be a bit more capital efficient, but it is not clear that better capital efficiency can explain the large delta between seed returns in tech and biotech.

Because these biotech companies were all acquired less than six years after Series A (with the exception of Moderna), we can’t know how valuable these companies would be if they had stayed independent for the same amount of time as the tech companies. We also can’t know how much more capital they’d need to raise. AveXis’ drug is approved and has generated better than expected sales and probably is profitable, but the rest of the companies still wouldn’t be near profitability if they were standalone companies. Moderna especially will require significant additional capital until it gets its first approved drug.

For what it’s worth, of the tech companies on the list, only Twitter and Zoom are profitable, and Zoom is basically breakeven.

Does this explain why tech returns are higher?

In the above chart on Series A returns, we saw that tech Series A investments in these very large companies generated on the order of 5-6x higher MOICs than Series A investments in these large biotech startups. Could that be explained by the fact that these tech companies get about twice as large as biotech companies on roughly the same amount of capital? Potentially. But it doesn’t seem like there is a dramatic difference in capital efficiency between tech and biotech companies based on this analysis.

But cash-on-cash returns from seed investments in these tech decacorns are orders of magnitude higher than in biotech. While the sample size is low, the biotech companies here are some of the best performing in the last several years, so it doesn’t seem crazy to say that these represent near the “peak” cash-on-cash returns for biotech seed investments. Order-of-magnitude level differences in seed returns probably can’t be explained by the above factors.

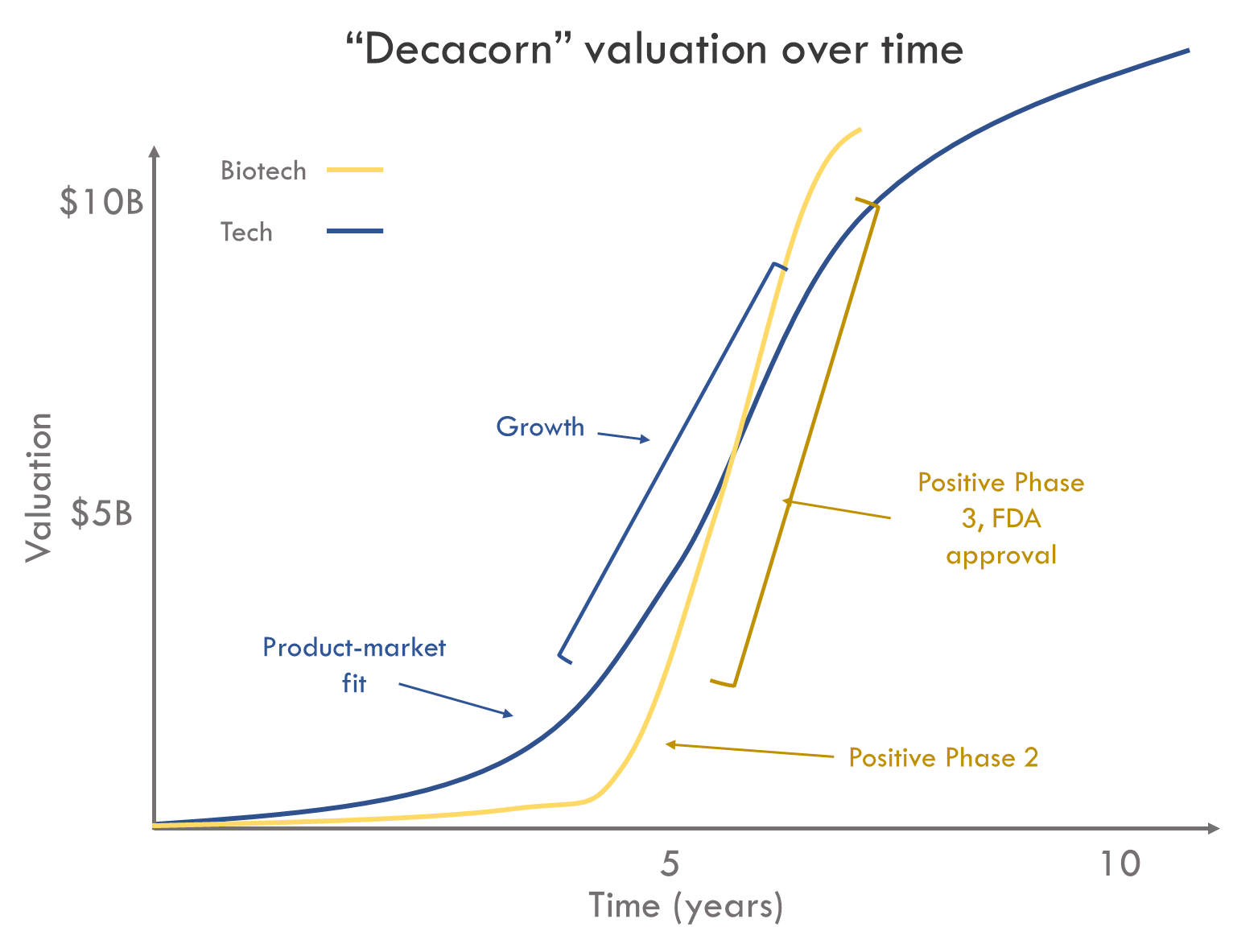

Timing of value creation

I think the most likely explanation for this difference is the timing of value creation in tech vs. biotech. The largest value inflection points happen later in biotech than tech. Specifically, human proof of concept, often in Phase 2 studies, is typically the biggest value inflection point in biotech. It takes years and tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to reach this point.

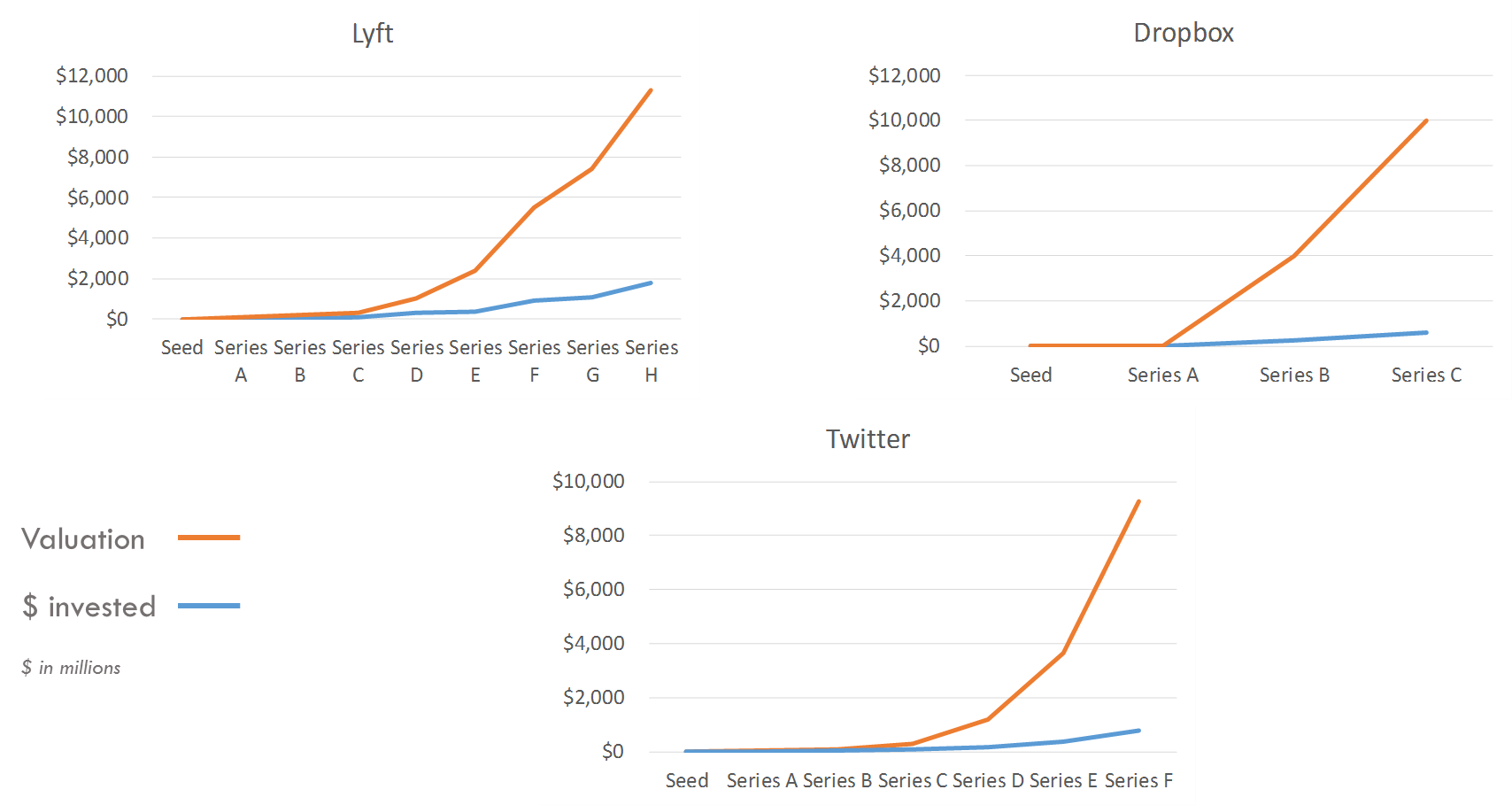

When we look at the growth of these biotech companies, we find that value is decoupled from investment later than happens for the tech companies:

If we look at the tech companies, we see that value separated from capital invested earlier:

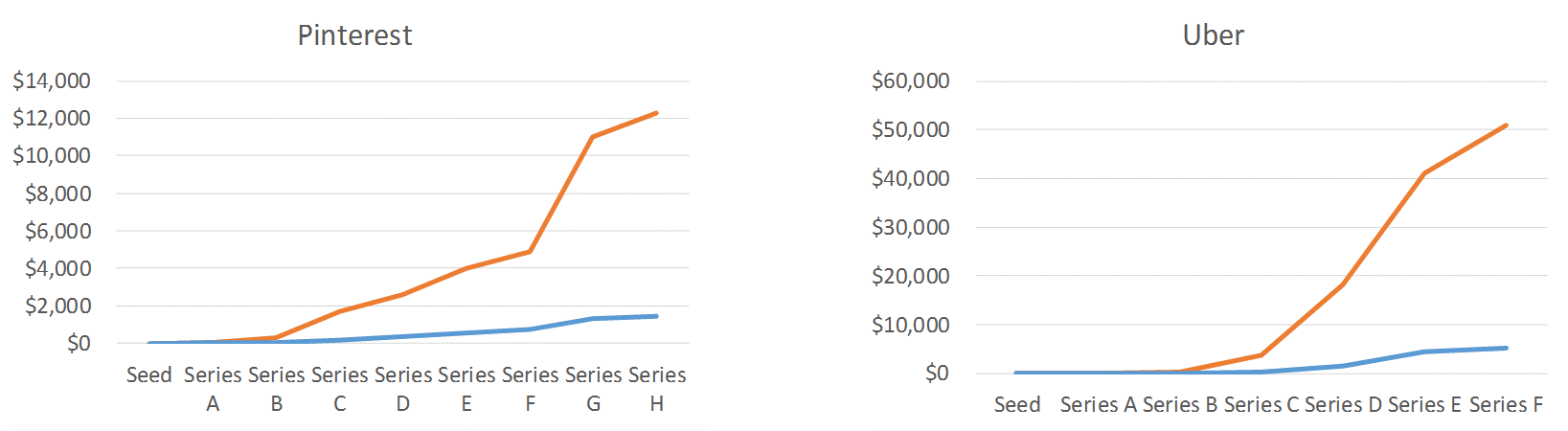

If we generalize this, we get a chart that looks like this:

Software companies can generate massive value inflection on pre-seed, seed and early venture rounds. A software startup with just a few engineers working from an apartment can get to product-market fit on a small seed round, and fuel exponential growth with Series A and B funding (that isn’t to say getting product-market fit is easy).

But in biotech, the slope of the growth curve doesn’t steepen significantly until human proof of concept. In biotech, the biggest risks are generally technical – will this drug work? This question cannot really be answered until mid-to-late-stage human studies. It costs tens or hundreds of millions of dollars and many years to reach this point.

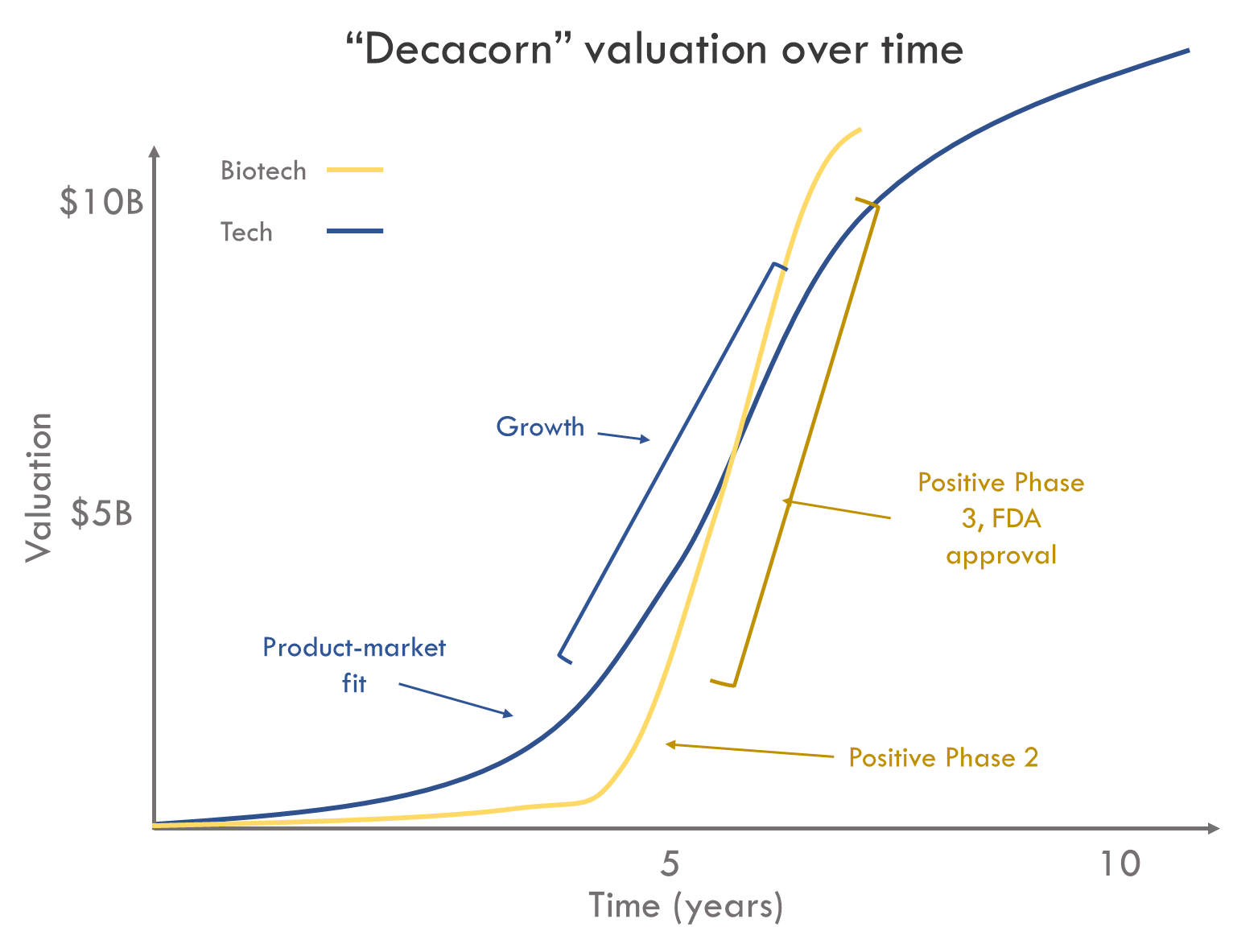

In another post, I calculated how the value of drugs changes as they advance through the development process. That post, based on data from a couple oft-cited studies of the cost of drug development, supports the idea that the biggest value inflection point in biotech is human proof of concept.

Improving returns in biotech

If it is true that the biggest value inflection in biotech occurs upon showing your drug is effective in humans, then the best way to improve returns in biotech is to reduce the time, cost and risk of demonstrating human proof of concept. There are many ways to do this: new biological discoveries that uncover relationships between pathways and disease, better chemistry or protein engineering to create best-in-class drugs against validated targets, new therapeutic modalities that enable therapies against previously intractable targets, better genomics and biostatistics to identify disease-related pathways and targets that are linked to human phenotypes, etc. It doesn’t matter what tool or technology you use, as long as you improve the chances your drug works in humans.

You don’t even need technology to do this – you can use strong biology combined with good business strategy to reduce the cost and risk of Phase 2 failure. That is, in fact, what biotech VCs have been focused on for the last decade or so. A big reason why VCs fund so many companies working on drugs for cancer, rare disease, and genetic disease is that you can get to human proof of concept faster, more cheaply and (in some cases) with less risk. The need to reduce risk of human POC is also why translational medicine, biomarkers, and well-validated targets are such key components of the biotech VC strategy.

In the next post, I’ll take a look at some of these top-performing biotech funds and examine their investment strategies. If you'd like to be notified when I publish this post, sign up to my newsletter below.

1 I have not compared Series C or later investments because only one of the biotech companies profiled (Moderna) raised a Series C. The other biotech companies went public after Series B. These days, biotech companies typically go public much sooner than tech companies (3-5 years for biotech vs. 7-10+ years for tech). In biotech, an IPO and subsequent public offerings are analogous to late-stage venture capital and growth equity in tech: they are financing events and provide some liquidity, but are not necessarily exits.

You may also like...

Top biotech VCs of 2018 and 2019

Valuing drugs and biotech companies

Venture returns from biopharma IPOs, 2018-Q1 2019

Valuations of biotech startups from Series A to IPO

Did you enjoy this article?

Then consider joining our mailing list. I periodically publish data-driven articles on the biotech startup and VC world.