How an unemployed 29 year old and a team of young scientists created the biotech industry

September 2019

There is no shortage of online content about how to start a tech company, but there is comparatively little on how to start a biotech startup. I recently came across an amazing set of interviews with the founders of Genentech that is the one of the best resources I've seen on biotech entrepreneurship.

In this post, I'll highlight 16 key quotes from early Genentech leaders and comment on how they can be applied to biotech startups today.

The interviews that these quotes came from were originally conducted as source material for Sally Smith Hughes' book Genentech: The Beginnings of Biotech. This book is a must-read for anyone looking to learn about the industry (it's a quick and engaging read as well -- I finished it in a day). The interview transcripts are worth reading in their entirety (especially the Bob Swanson and Dave Goeddel interviews) and are available for free online through Berkeley's Bancroft Library Oral History Center1.

Early Genentech at a glance

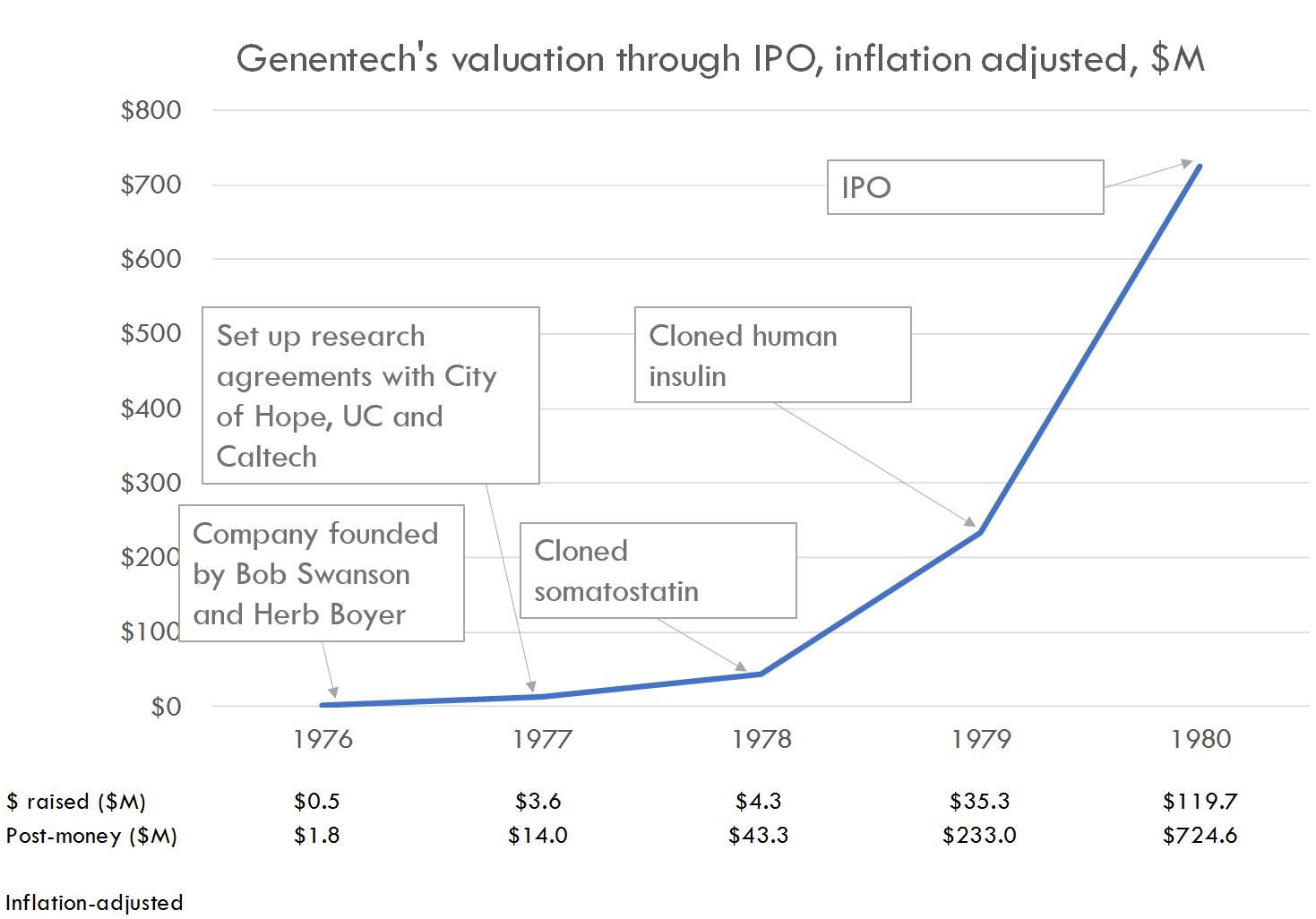

To set the stage, here is a chart with major value inflection points during the early days of the company. At this time, Bob Swanson, the founding CEO, was in his late 20s / early 30s, and most of Genentech's scientists, led by Dave Goeddel, were also in their 20s and 30s. Bob's co-founder, UCSF professor Herb Boyer, was more experienced, but he took a fairly hands-off approach to the science. Prior to starting Genentech, Bob had been laid off by venture fund Kleiner Perkins.

Genentech was created to use emerging genetic engineering technology to create new medicines. When the company was founded, genetic engineering was a new and relatively unknown field. The leading scientists in the area thought it would be years or decades before genetic engineering was advanced enough to create medicines. Big pharma companies were universally dismissive of the technology.

The venture capital and startup industry was also in its infancy. There was no such thing as a biotech startup, and there hadn't been a new pharma company created in decades. Kleiner Perkins, one of the first venture capital funds, had just started (Bob was an early employee of the fund). Apple was founded on April 1, 1976, less than a week before Genentech was founded.

(As a side note, Apple and Genentech have always been somewhat linked. Steve Jobs and Bob Swanson were the original young tech entrepreneurs. When Genentech went public in 1980, it was the biggest tech IPO ever -- until Apple went public months later. Art Levinson, who took over as Apple's chairman after Steve Jobs passed away and was on Google's board from 2004-2009, was an early employee at Genentech and was Genentech's CEO in the 1990s and 2000s).

Overview of early Genentech's strategy

Genentech's strategy was to first prove that the technology could work -- that bacteria or yeast could be engineered to make human proteins -- and then to use genetic engineering to make products. They proved the concept by getting bacteria to produce somatostatin, a small hormone. Somatostatin wasn't useful as a medicine, but it was a relatively simple molecule to make with their tech and thus a good proof-of-concept.

Genentech's first major product was recombinant insulin. At the time, insulin was obtained by killing pigs or cows and extracting it from their tissues. This was an expensive and potentially less safe approach than producing human insulin from bacteria or yeast. Cloning insulin put Genentech on the scientific and financial map and kickstarted the biotech industry.

With that context in hand, here's how Genentech approached building a biotech startup:

Create value by eliminating risk

Bill Hambrecht…has said the only common characteristic he has noticed in the successful entrepreneurs he's invested in has been that they're all basically conservative…they're willing to go for it, but everyone is looking at how you minimize the risks as you're doing so.

- Bob Swanson

In most industries, companies create value by growing revenue or profits. In biotherapeutics, companies cannot sell products until FDA approves them, which can take years. But pre-revenue drugs can still be immensely valuable. In development-stage drug companies, value is created by eliminating technical risk.

Like many other entrepreneurs, Bob had a unique attitude toward risk: part risk-averse, part risk-seeking. In the words of Josh Wolfe, co-founder of Lux Capital, "entrepreneurs aren't risk takers. They're risk killers".

Build a "staircase of value"

I tried to organize things so that once you had success and created value in the company, then you raised the next round of money for the next success that would create greater value…. So it's sort of building a staircase…to the point where your cash flow is positive from product sales.

- Bob Swanson

Bob's goal from the beginning was to build a fully integrated pharma company -- one that developed and sold its own products. He broke this goal into small units of value creation, and raised a new round of capital to fund each unit.

"Make something people want"

This is the essence of a company. The better you understand customers' needs…the more value the product has that they're willing to buy. Then you make more money, and the more money you make, the more it says, "I'm doing things right. I'm a healthy company.”

- Bob Swanson

Bob understood that the success of the company depended on its ability to create value for customers. In the words of Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator, "make something people want".

This holds true in biotech today. Understanding a patient's condition, the available treatment options, and unmet clinical needs is the starting point for developing a drug.

Science first

One of the reasons companies succeed or fail is which projects get cut and which ones don’t…. It's a judgement call, and that's where you need the very top scientists and medical doctors and everybody to make that call--when to stop it, when is enough, and when to go the next round.

- Bob Swanson

Genentech focused on recruiting the best scientists and creating a culture that prized science above all else. Genentech needed the best scientists because it was working in a competitive, cutting edge field, but also knew that the company needed to be rigorous and scientific in its business decision making.

Scientists first

Bob Swanson: Boyer's idea was…"Let's give [the young scientists] the credit." He didn't put his name on the insulin paper. And that, for a postdoc, is pretty attractive, rather than having your boss trying for the credit all the time and to keep you as the worker….

So the advantages were freedom from seeking out grants, a chance to be owners of the company.

Sally Smith Hughes: Could you in addition to the equity offer them higher salaries than they were making in academia?

Bob: Oh, yes. Postdocs continue to be very poorly paid. So yes, we could offer them good salaries.

To recruit the best scientists, Genentech combined the best attributes of academia and industry. Genentech gave scientists the opportunity to work on important scientific problems, a large degree of freedom, and encouraged them to publish their results. At the same time, Genentech gave credit based on merit, not seniority, paid scientists much more than they would make in academia, and issued stock grants that could provide life-changing financial gains if the company succeeded.

Work on ambitious problems

We don't work on any projects we can't get someone excited about…I think the key to any organization is hiring outstanding people, and helping them get excited about what they're doing.

- Bob Swanson

Genentech's ambition was key to recruiting and motivating the best scientists. As Sam Altman says, "It’s easier to do a hard startup than an easy startup. People want to be part of something exciting and feel that their work matters."

Products before platform

We were very focused on products, and that made a big difference. I know Cetus at the time was more into developing the technology. I said, "Well, let's make a product, and we'll develop the technology we need to make the product, and let the product drive the science, rather than the other way around." Actually, we wound up doing better science because of that, and also we got a product.

- Bob Swanson

Genentech was developing arguably the most powerful tech platform in the history of pharma, but it didn't focus on building a platform. Genentech focused first on products, and built their platform to support product development efforts. This ended up being a better strategy for developing the platform than putting the platform first.

In the words of Bruce Booth, VC at Atlas Venture, “[platforms] aren’t “science projects”…the path to product candidates is generally known at company inception, and the key emphasis is on validating that the platform can generate repeatable advances”.

Test the science with killer experiments

Riggs and Itakura convinced us that the first thing we should do was somatostatin. They said, "Look, it's just going to be too technically difficult to do insulin to start with. Let's make somatostatin. It's smaller; we can do that one, and then based on that demonstration, we'll have proven the technology. And then we can go to the next level.

- Bob Swanson

It is common nowadays in ventures to plan, as Bob did then, to take more money after risk is reduced by achieving some financeable benchmark. In fact, Tom Perkins very recently reminded me of one of his key tenets for investment. That is, design an experiment that can establish quickly whether the technology is feasible--fail fast.

- Tom Kiley, Genentech corporate counsel

Bob wanted to race forward with developing insulin rather than first testing the technology by making a simpler molecule. However, his scientists convinced him that they should first try to clone somatostatin. This was a cheaper and faster way to figure out if the science worked. This can be thought of as a "killer experiment", a key early experiment "to demonstrate the scientific robustness of the founding concept as cheaply as possible” (from Bruce Booth).

Choose the right initial product

Diabetics were getting pig or cow insulin.…. And we believed people would rather have human insulin than pig insulin. So we said, "Okay. As best we can tell today, there's a big need." Lilly was selling $400 million [$1.8B in 2019 dollars] worth of insulin a year. It's a small [peptide] molecule; it was probably somewhat technically feasible based on what we knew. The economics looked pretty good. If we did it, it could be patentable.

- Bob Swanson

The first product was insulin: there was a well-validated unmet need for safer, cheaper insulin; the product was technically feasible (small peptide vs. more complex protein); the economics were good; it was patentable.

Focus on validated targets and biology

In theory, you could cure cancer, or you could do this or that, and if you could that would be great. But it was certainly more risky because you didn't understand the biology the same way that you understood the potential market….

We chose to develop [insulin and growth hormone] first because at this early stage we couldn't afford to take any of those risks. If we succeeded in making these products, we had to know that they would work in humans.

- Bob Swanson

Genentech knew that human biology was complicated and initially focused on making molecules with well understood medical properties like insulin and growth hormone. They knew that if they could make these drugs, they would be effective in treating disease. If they had focused on newer or unproven biology, they would add another major risk on top of the already significant technical risk.

Prioritize products with quick path to clinical proof of concept and FDA approval

In the insulin case, it was easy to say, Okay, is it safe? Is it reducing the level of glucose in the blood? As opposed to some of the other FDA criteria which were more difficult to satisfy at the time. At the time, they were requiring survival to prove a new cancer drug, so you had to do long studies and show survivals. Even arthritis: is your hand feeling a little bit better? It's not as easy to measure, and probably would be longer and more difficult for approval. So thinking about how quickly something could go through the regulatory process was a key part of the product selection.

- Bob Swanson

The biggest risk in drug development is that a drug that works in animals doesn't work in humans. Because value is tied to risk reduction, the single biggest value inflection point for most biotherapeutics companies is demonstration that the drug is effective in humans. Picking products where you can reach this point quickly and on an affordable budget is critical.

It is also critical to understand the regulatory process in advance. A clear and fast FDA pathway can be the difference between a product being uninvestable and a no-brainer. Regulatory incentives are a big reason why most new drugs are developed for cancer and rare disease.

Develop your own products rather than licensing early-stage assets...

If you sell something in the pharmaceutical business… typically, your margins are in the 85 or 90 percent range. At that time, pushing 8 or 10 percent was thought to be an outrageous royalty rate. One way or the other, you've got enormous research risk. So…it's a better return if you're able to make it and sell it yourself.

- Bob Swanson

Genentech's goal was always to sell their own products. They knew that the value of a drug increases exponentially as it advances through development. When you partner too early, you give up reward without reducing risk.

...but license where appropriate

There were something like 250,000 doctors around the country. So a small company like ourselves couldn't market [insulin] to all the physicians and explain and detail the products. But in the case of growth hormone…there were only about five hundred pediatric endocrinologists around the country…. So [that was] the beginning of our entry into selling products ourselves.

- Bob Swanson

Insulin was just a step on the value staircase for Genentech: a way for them to advance their technology, create value, and raise money to create more value. The market for insulin was too big for a small company to pursue as its first product. So they sold the rights to Lilly and got cash to fund the next step of their plan to build a fully integrated pharma company.

Try to be profitable as early as possible

We tried to get partnerships or funding from companies to cover our operating expenses.…The idea was, if you could have contracts to fund your costs of everyday research, then you could raise money with more flexibility… as opposed to being at the mercy of the investors. So that was a very important strategy, and basically from 1978 on, we were profitable.

- Bob Swanson

The Lilly partnership was one of many deals Genentech did to mitigate financing risk. Financing risk was – and still is – one of the biggest risks for drug companies that are years from revenue.

It seems absolutely crazy that a major goal at early Genentech was to be profitable. Today most software startups don't initially focus on profitability, and a profitable biotech startup is unheard of. But Bob knew that venture financing was unreliable -- at that time, the venture capital industry was just getting started -- so he did non-dilutive corporate partnerships to fund the company.

Don't overspend

It didn't make sense to me that we should fund, build, put money into facilities for Genentech because nobody knew yet if the science was going to work. Let's fund research at the universities and get the rights to the patents.

- Bob Swanson

Another important way to mitigate financing risk is to be capital efficient. Another Bruce Booth quote is relevant here: “We are disciples of strategic capital efficiency…. We want to see lean organizations, scaled appropriately for their strategy.”

Get things done

Sally Smith Hughes: Kleiner & Perkins funded the first phase…. What motivated them?

Bob Swanson: Making more money.

Sally: Yes, but why with you? It was an untried technology and, from what you've said, they must have had some doubts about you.

Bob: Well, see, everything I said I was going to do, I did.

As an unproven entrepreneur working on a crazy idea – a successful, independent biopharma company hadn’t been created in decades – Bob had to prove to investors he could get things done with an extremely limited budget. He and his team worked relentlessy to create value, and their success convinced investors to take them seriously.

A playbook for biotech entrepreneurship

It is uncanny how well the Genentech playbook has aged, and it is amazing that Bob, a 29 year old, was able to so deeply understand the complex pharma industry as a complete outsider. The playbook he developed seemingly from first principles is still the one that biotech startups follow today. While there may be some hindsight bias from these quotes (these interviews were conducted in 1997, about 20 years after Genentech was founded), Genentech's success is clear evidence that Bob knew what he was doing.

While biotech veterans are surely familiar with the Genentech story, the next generation of biotech entrepreneurs is not familiar with this history. Biotech had a rough decade in the 2000s, and a generation of scientists grew up at a time when biotech entrepreneurship simply wasn't a viable path. With biotech's resurgence over the last few years, hopefully a new generation of entrepreneurs can appreciate the lessons of the industry's history.

Benchmark investor performance

Deal-level returns, check sizes, performance metrics, portfolio overviews and more for thousands of public and private biotech investors.

Here's the TLDR version:

- Create value by eliminating risk

- Build a "staircase of value"

- "Make something people want"

- Science first

- Scientists first

- Work on ambitious problems

- Products before platform

- Test the science with killer experiments

- Choose the right initial product

- Focus on validated targets and biology

- Prioritize products with quick path to clinical proof of concept and FDA approval

- Develop your own products rather than licensing early-stage assets...

- ...but license where appropriate

- Try to be profitable as early as possible

- Don't overspend

- Get things done

You may also like...

The case for young founders in biotech

Valuing drugs and biotech companies

Valuations of biotech startups from Series A to IPO

List of recently funded biotech startups

Bay Bridge Bio Startup Database

Did you enjoy this article?

Then consider joining our mailing list. I periodically publish data-driven articles on the biotech startup and VC world.

1 Oral histories conducted by Sally Smith Hughes for the Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2003. Accessible at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/oral-history-center. Quoted with permission according to "fair use" standard: http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/libraries/bancroft-library/oral-history-center/rights