Biopharma VC Basics 2: How do VCs work?

Richard Murphey, 2/7/2018

In the first part of this series, we discussed the role of venture capital in the biotech ecosystem and the economy at large. In this post we’ll discuss the basics of how these VCs work.

Who do VC's serve?

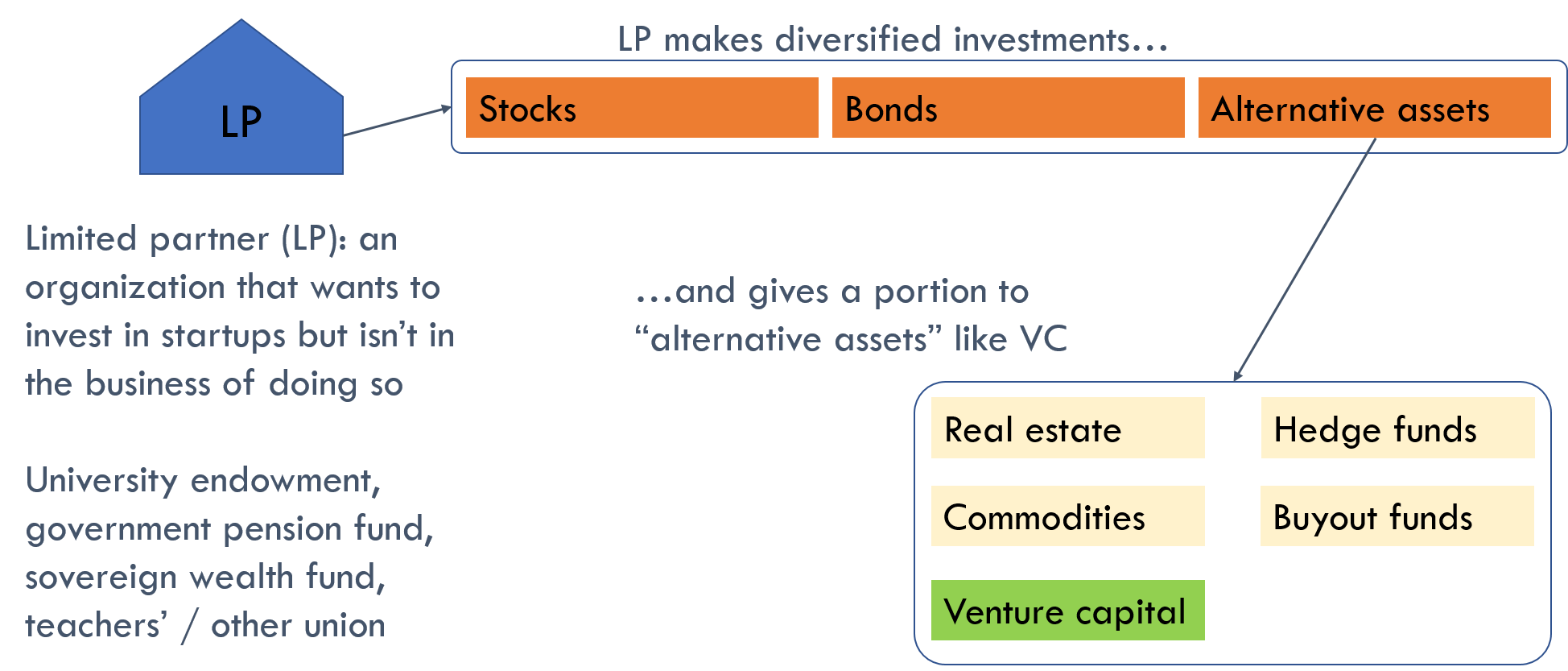

A VC's job, in blunt terms, is to turn a pile of money into a bigger pile of money. VCs do this on behalf of clients called "limited partners" (LPs). LPs of venture funds are institutions that 1) have a lot of money, 2) want to invest some of that money in startups and 3) are not in the business of investing in startups. LPs are generally organizations like pension funds, university endowments, foundations, or other financial institutions (including even other venture funds). LPs hire VCs to help them manage their money, VCs take a cut of the profits they make, the LPs also take a cut to pay for their administrative costs, and the rest of the money helps pay for employee or government pensions, university operations, etc 1.

LPs want to maximize the return on their investments while minimizing risk. A key to this strategy is diversification: LPs invest in a diversified portfolio of assets, including stocks, bonds and “alternative assets”. LPs invest in alternative assets, like real estate, hedge funds, commodities and venture capital, because these can offer higher returns and also can be uncorrelated with stocks and bonds, which helps to reduce risk (for example, a hedge fund might have a strategy that increases in value when most stocks go down).

VCs invest in startups and make money when startups “exit”

So limited partners hire VCs to profitably manage (ie invest) their money. The VC does this by investing in startups that it thinks will grow in value. In return for their cash, VCs get “equity”, which represents a share of the ownership of the company – basically the same thing you get when you buy a stock on the stock market, except startups are “private” companies: you can’t freely buy and sell shares on an open market like you can for Google or Apple (or even Bitcoin) 2. The reasons for this are complex, but essentially startups are very high risk, so only certain types of investors can invest, and being a “public” company that can sell stock on open markets requires a lot of investment in compliance and other administrative things that startups frankly don’t have time or money to deal with.

If you or I purchase shares of a publicly traded company, and those shares go up in value, we can sell the shares immediately and capture profit. The ability to buy and sell shares on demand at a given price is called “liquidity”. The easier it is to buy and sell shares quickly at a given price, the more “liquid” a market is. Stocks in big companies like Apple or Google are liquid investments. A house is an illiquid investment. VC investments in private startups are even more illiquid.

The VC can only generate profit 3 on its investment through an “exit”: when a big company buys a small company for a higher price than what the VC paid, or when a startup goes public through an IPO, and the VC can sell shares on an open market. Startups try to exit within 5-7 years after an investment is made, although most startups do not end up being profitable investments. But the few startups that are profitable are so profitable that they more than make up for the many unprofitable investments (at least that's the goal; in reality many funds don't make a profit and ultimately go out of business).

After the VC invests the money and generates profits on the investment (again, most investments will not be profitable), it returns the money plus profits minus fees to the LPs. This cycle of an LP giving money to a VC, a VC investing in startups, startups “exiting” (or failing) and VCs returning money to LPs generally takes 10 years: ~3 years for a VC to invest the money that LPs give it, and 5-7 years to “harvest” returns via exits. In fact, the contractual agreements between VCs and LPs can require VCs to return the LPs' money after 10 years.

Following the money

So what kind of numbers are involved here? Let’s take a look using some numbers for a hypothetical venture capital fund investing in life sciences.

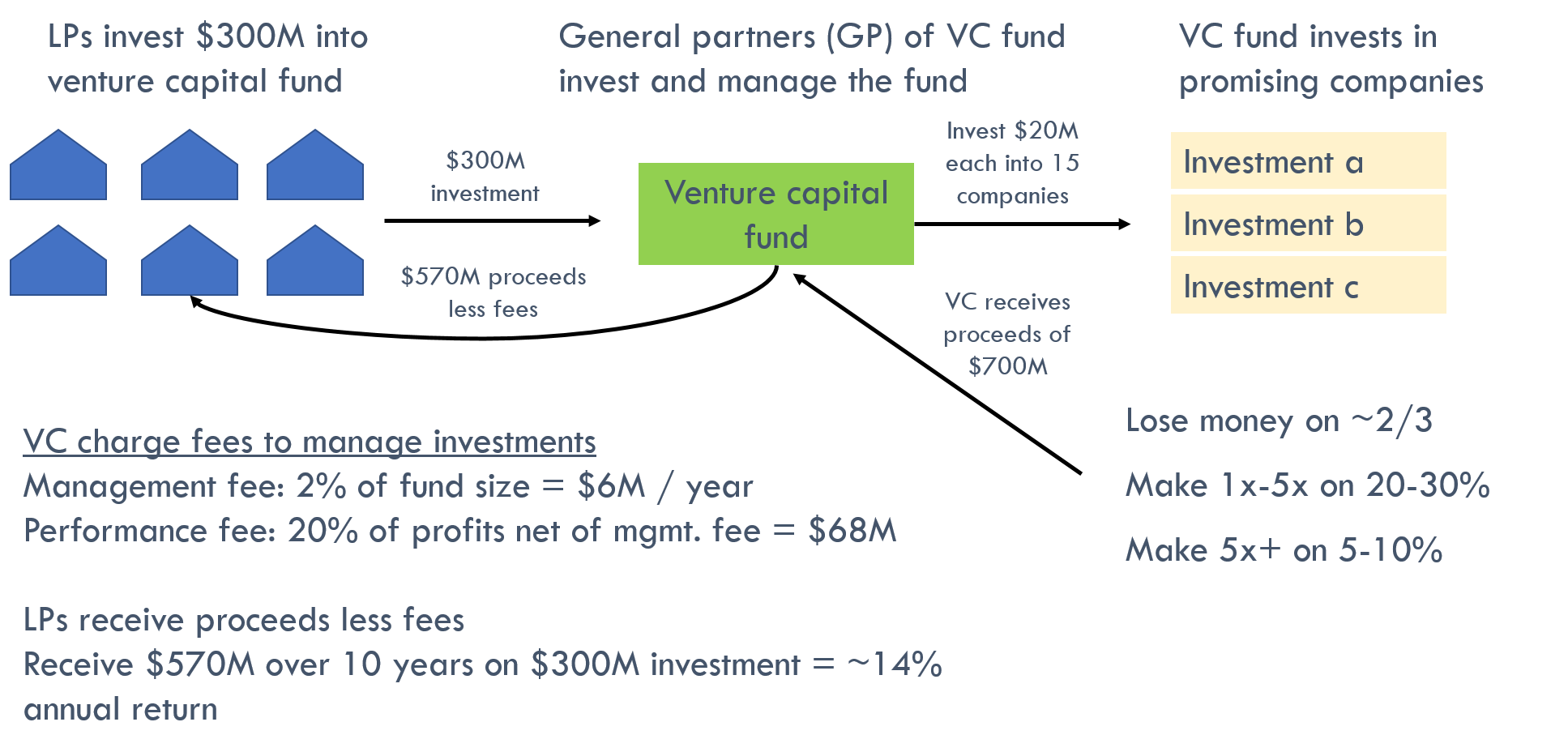

Let's call our hypothetical venture capital firm Berkeley Ventures. Berkeley Ventures is an organization with a few managers, called “general partners”, and their employees. Let’s assume a group of LPs wants to give Berkeley Ventures $300M to invest. Berkeley Ventures creates a fund (basically a separate legal / business entity that houses the $300M) called Berkeley Ventures Fund I (funds usually use Latin letters for some reason). Berkeley Ventures may manage multiple funds (Berkeley Ventures I, Berkeley Ventures II, etc), but each fund has a specific set of LPs and rules around how it is invested. Berkeley Ventures Fund I invests exclusively in life sciences.

To raise this $300M, Berkeley Ventures convinced LPs that they would turn that $300M into, say $900M over 10 years (VCs typically aim to get a 3x return on their funds over a ~10-year period). They convinced LPs to invest with them by showing how successful at investing they had been in the past, creating a convincing strategy for how they would invest the money, describing the investment opportunities they saw in the market, and touting their advantages versus other venture firms like Stanford Ventures.

The LPs liked the story and agreed to pay Berkeley Ventures 2% of the $300M as an annual fee for managing the LPs’ money. So Berkeley Ventures gets $6M a year to pay for employee salaries (maybe 5 senior general partners, 4 junior level investors, and 7 other / administrative personnel), office space, travel, IT, etc. Not bad.

But the LPs don’t want Berkeley Ventures to sit there and collect $6M / year for 10 years. They want Berkeley Ventures working as hard as possible to make money. To incentivize them, the LPs let Berkeley Ventures keep 20% of the profits from their investments. This share of the profits is called “carried interest”, or “carry”. Typically, the general partners (or GPs -- these are the people who manage the fund), get most of the carry. GPs also often have to invest some of their own personal money into the fund so the have "skin in the game". Junior level investors may get some carry as well, but generally much less than the GPs.

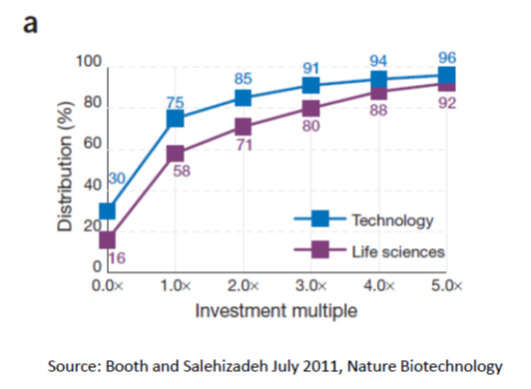

With the terms of the arrangement settled, Berkeley Ventures sets out to invest this money. Let’s say the profitability of their investments is typical for the industry (as of 2011 at least; things have changed a lot since then but this 2011 data was convenient to use as an example), per the chart below:

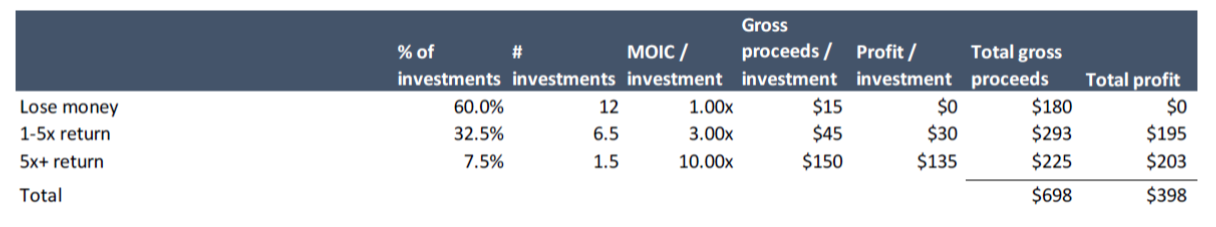

The “investment multiple” is simply (proceeds from investment / money invested). So 58% of Berkeley Ventures’ investments lose money (ie have an investment multiple of under 1.0x). Roughly 1/3 of their investments make a decent amount of money (1.0x-5.0x investment multiple). However, 5-10% of their investments make a lot of money: over 5.0x the amount originally invested (for the sake of simplicity I assume these deals generate 10x multiples; the best companies can generate 30-100x+ returns, and these outliers can determine an entire fund's performance; the recent $11B acquisition of Kite and $9B acquisition of Juno saw one fund turn $4M into $420M and another turn $45M into $1B)4.

This is what Berkeley Ventures' returns look like after they invest all their money and all of their investments either "exit" or fail, assuming they do 20 investments and invest $15M per investment:

So Berkeley Ventures turned $300M into almost $700M over 10 years. They collected $60M in management fees (2% * $300M per year * 10 years), and collected ~$70M in carry (shared profits). So the LPs get $570M after fees ($700M in gross proceeds minus $130M in management fees and carry). Over 10 years, that comes out to ~14% annual return (the returns calculation assumes the fund deploys capital over a five year period, then generates proceeds from exits over the next five years).

Is that good? The historical annual return for the S&P 500 is about 10%, so it is higher than that. However, venture capital is riskier than investing in the S&P 500 (a basket of 500 large companies), so VC should have a higher return to make up for the higher risk. This isn’t really that great of a return, and the best funds generate much higher returns than this. But 2011 was a pretty dark time in life science VC.

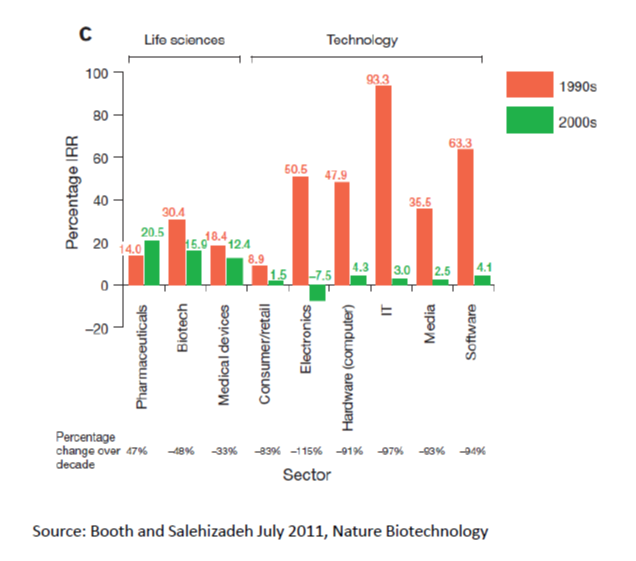

Is this indicative of what really happens? Again, we’ll use a 2011 paper by Bruce Booth, a prominent early-stage life science VC:

The 14% annual return seems about right for life sciences. But wow, look at tech in the 1990s!! And then look at it in the 2000s….

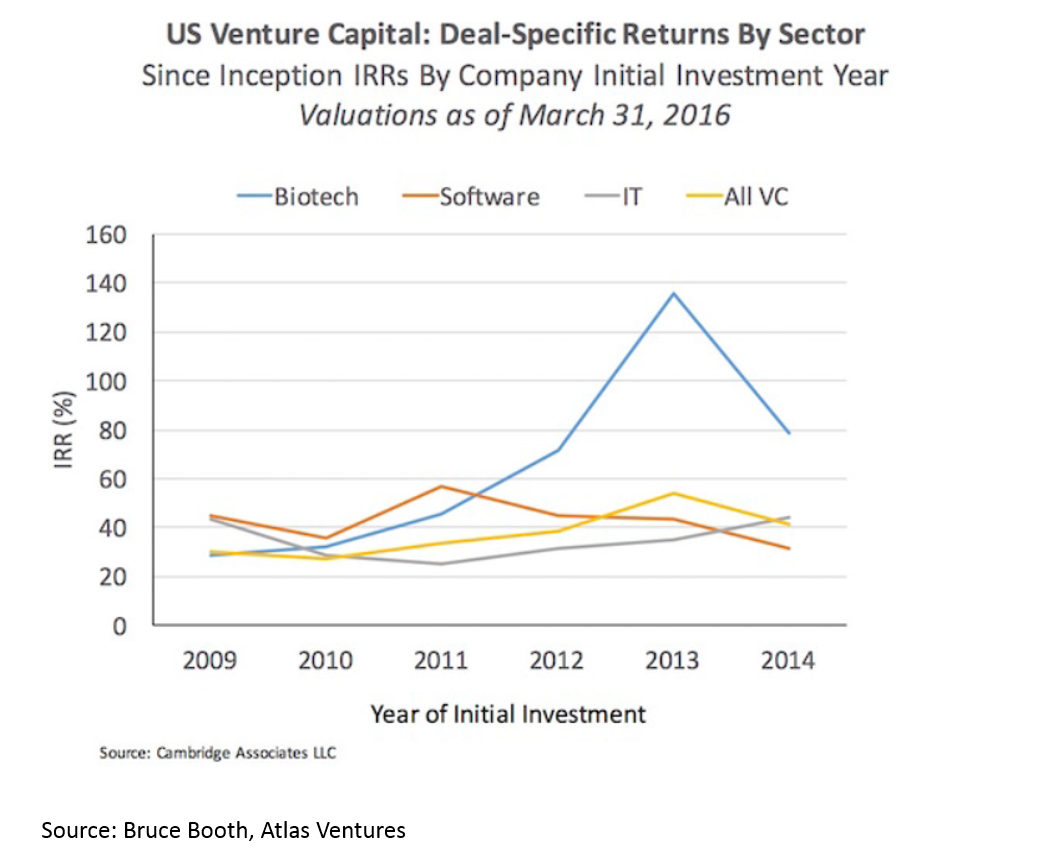

Back in 2011 when this data came out, VC was in a rough patch, and life sciences VC was in one of its worst periods ever. But things have changed since then, a LOT. Life sciences, and biopharma in particular, has generated incredible venture returns (for an explanation of the reasons why, see here):

Is there a biotech bubble? I don't think so, but that is a discussion for another post. But the last few years have been a good time to be a biopharma VC or LP.

1 The VCs described here are “institutional VCs”. There is another group of VCs called “corporate VCs”. Corporate VCs manage money on behalf of companies like Google, Pfizer, GE, etc. While part of a corporate VCs’ job is to turn a pile of money into a bigger pile of money, they have other jobs as well related to their company’s mission, whether it is identifying companies that they might want to acquire later, keeping up-to-date on technological trends, or establishing relationships with leading researchers in an area of interest. In biopharma, corporate VCs account for 20-30% of all venture investments. So while they are a smaller part of the VC industry than institutional VCs, they are an important part of the ecosystem.

2 VCs typically invest in a type of equity called “preferred equity”, which is a certain type of equity with a few extra rights compared to normal “common” stock you or I might buy in a public company.

3 I'm using the term "profit" a bit loosely here. The technical financial definition of profit refers to money that's left over after you subtract expenses from revenue. Profit is thus an item in the "income statement" (aka "profit and loss" statement, or "P&L"). Investors generally refer to proceeds from their investments as "returns", not "profits", but I use the term "profit" as I think it's a bit more familiar to non-finance audiences.

4 In tech VC, and even in biotech VC in the last five years, outlier companies can be hugely successful and returns even more highly concentrated into a small number of companies. In some cases 10% of companies can generate 90% of a fund’s returns.