The biotech VC crunch

April 11, 2023

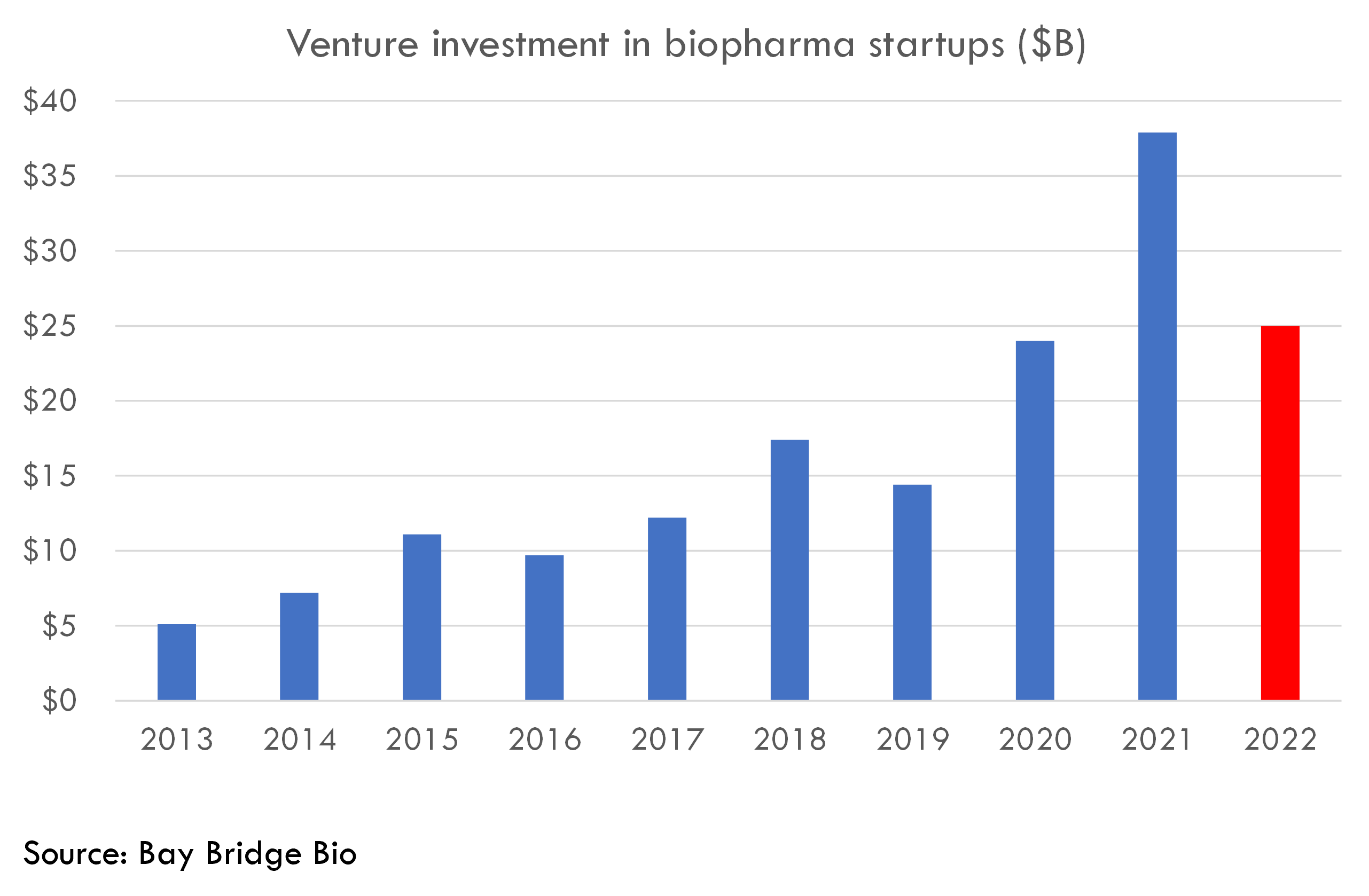

Huge amounts of money have flowed to biotech startups over the last decade. But that trend may be reversing -- in a big way.

Biotech markets have been rocked by rising interest rates in the last two years. The early stage venture and seed market has thus far withstood the worst of this turbulence, but 2023 may be the year that disruption comes to early stage funding markets.

To understand how interest rates, macroeconomic trends, and public market disruption impact biotech startups and VCs, we have to understand the biotech startup money machine.

The biotech startup money machine

The biotech startup money machine starts when venture capitalists invest in private biotech startups.

VCs make money when these private companies grow and ultimately go public or get bought by bigger pharma companies.

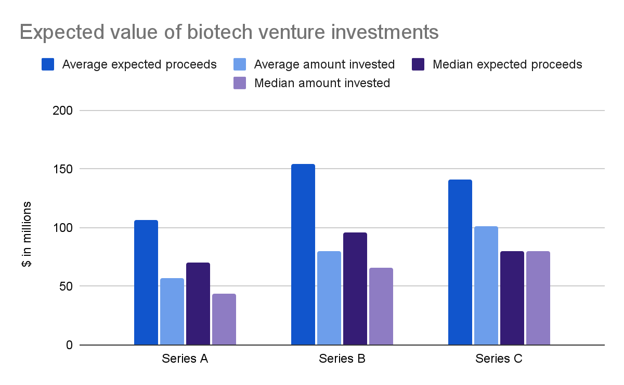

Over the last few years, biotech venture investors as a whole have made 1.5-2x cash-on-cash returns from this money machine. And they’ve generated these returns across a 3-5 year time frame, resulting in IRR of 15-25%.

That is a great return, especially when interest rates are 0%, and that return is generated across the entire asset class – tens of billions of dollars of investment per year – not just the outlier funds.

The biotech IPO machine

These returns were driven by a hot IPO market. In the last few years, it was much easier for biotech VCs to make money by flipping startups to IPO than selling to pharma.

So how did the IPO machine work (I use past tense because, as you probably know, the IPO market has stopped)?

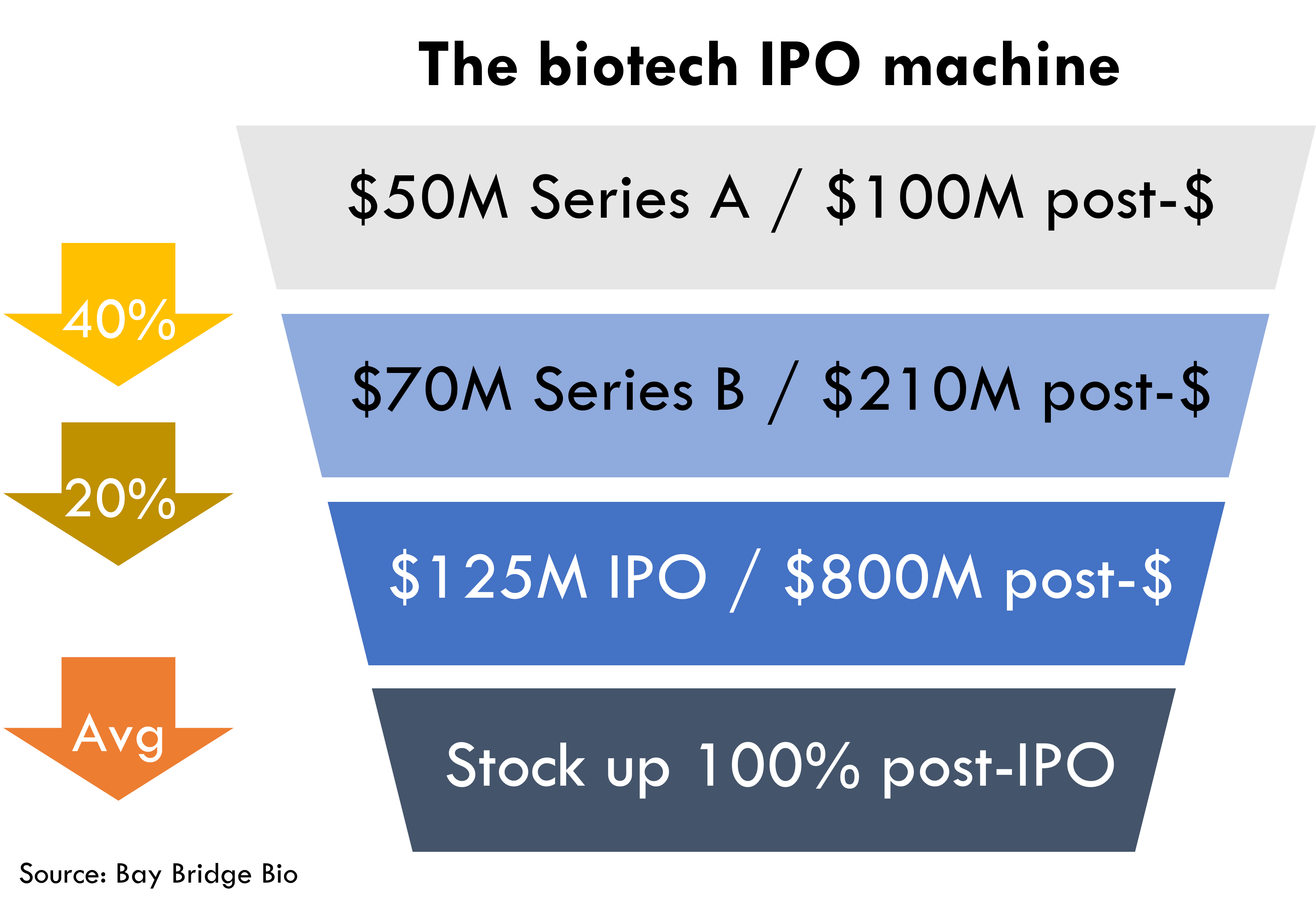

The machine starts when VCs invest in a Series A round. Generally VCs invest around $50M to acquire about half of the company, resulting in a post-money valuation of around $100M.

Of those companies, 40% of them end up raising a Series B round (the rest get acquired, go public before raising another private round, or become zombie companies). Typically this is around $70M invested, valuing the company at $210M.

Then 20% of those Series B companies go public after the B round at a valuation of $800M (and another 20% go public after raising a Series C).

But VCs don’t sell their stock right away, they generally wait a few years. Let’s assume the average IPO is up 100% a year or so after IPO (during the height of the IPO bull market, this was close to reality).

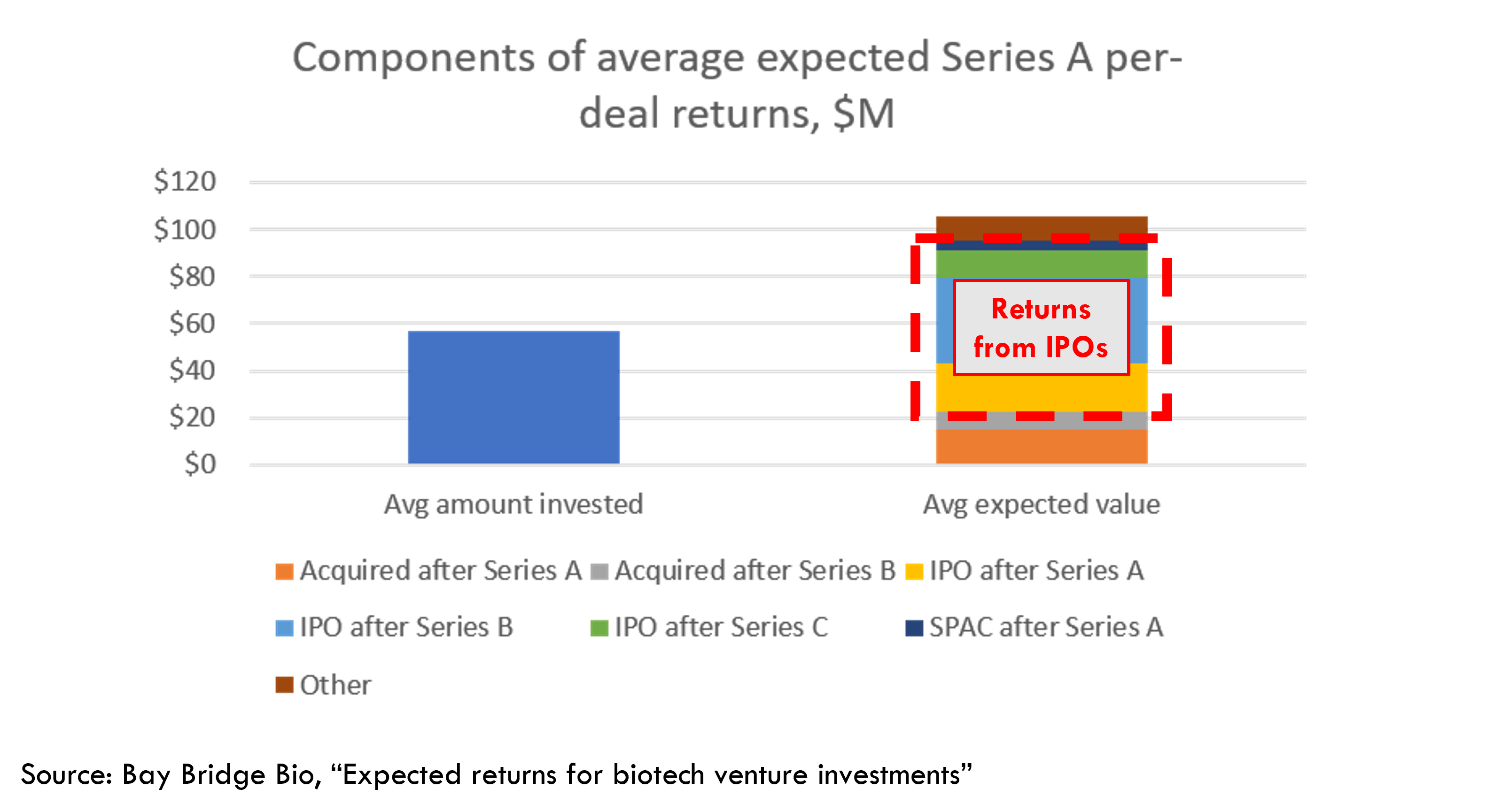

This all adds up to a return to Series A investors to about 1.5x from the IPO market alone (recall the total returns of Series A investors are around 1.5-2x).

Defensible clinical trial cost estimates

Get transparent cost estimates for any trial in minutes. Input an NCT ID or upload a protocol, then see a full cost analysis report.

As we see, the IPO market was responsible for most of Series A investors’ returns.

Which is a problem when the IPO machine breaks. And break it has.

The IPO market is down nearly 90% from 2021 to 2022. All else equal, this drives expected returns from IPOs from 1.5x to 0.1x.

There are simply not enough IPOs to return all the venture capital that has been invested into startups.

Other options for biotech startups

If IPO is no longer an option, that leaves biotech startups with four choices: get acquired, raise private capital, partner with big pharma, or get to profitability and no longer need outside funding.

The last option – getting to profitability – isn’t a real option for most therapeutics companies that need to raise tens or hundreds of millions to get a drug approved.

What about M&A?

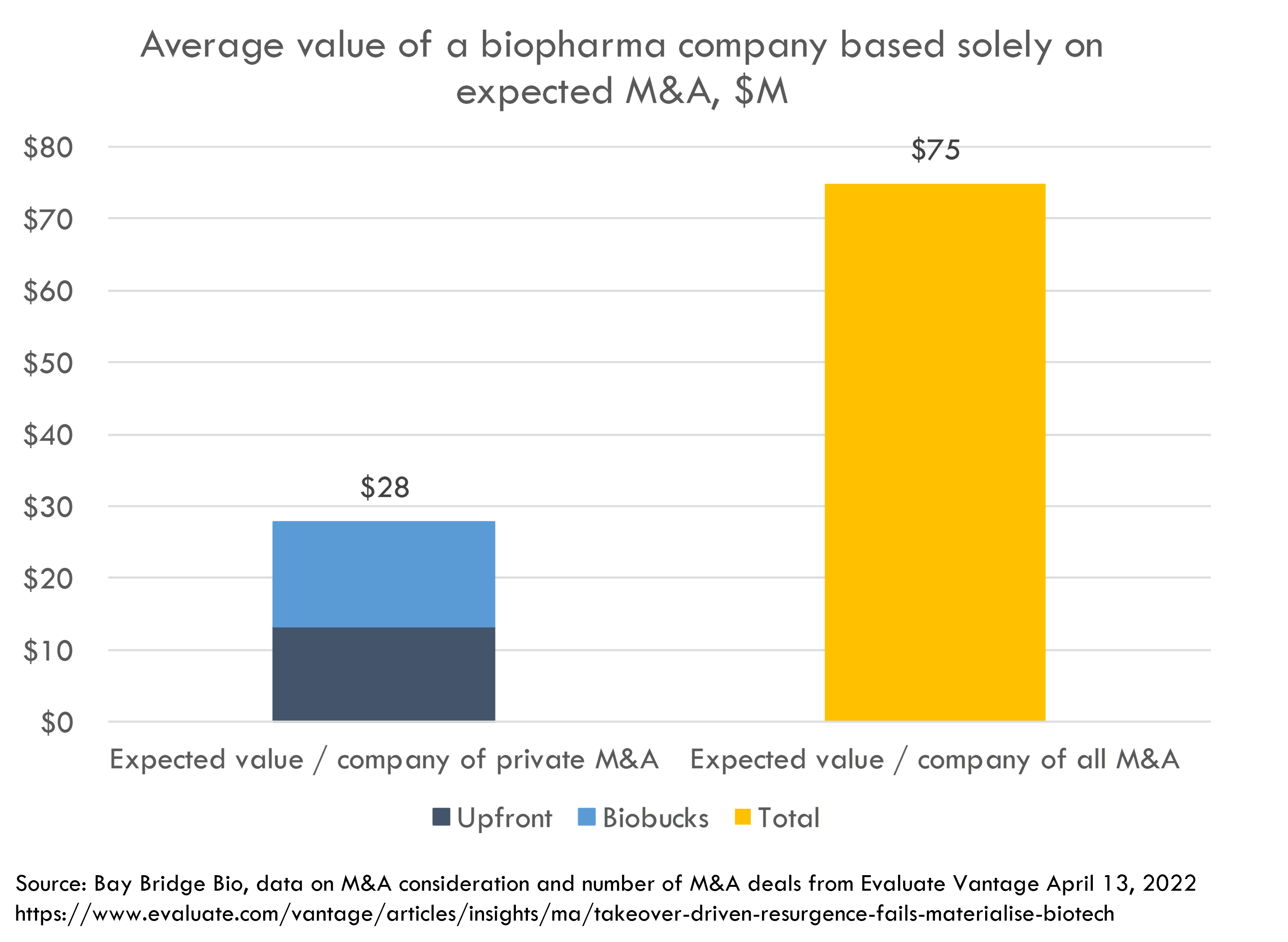

The M&A option is also not enough. The amount of money big pharma spends on M&A has been relatively constant in the last few years, while the number of startups – and their valuations – have skyrocketed. If big pharma continues to spend the same amount on startup M&A as they have in the past, they only have enough to buy around 10% of each startup.

That’s not enough to return investors’ capital – much less to generate compelling returns.

What about raising private capital?

Unfortunately, raising private funding is also challenging. VCs have a lot of dry powder, but they are not deploying much of it towards new investments. Late-stage funding has dried up, so VCs need to reserve more capital to support their existing portfolio companies. And they have to cover a big funding gap.

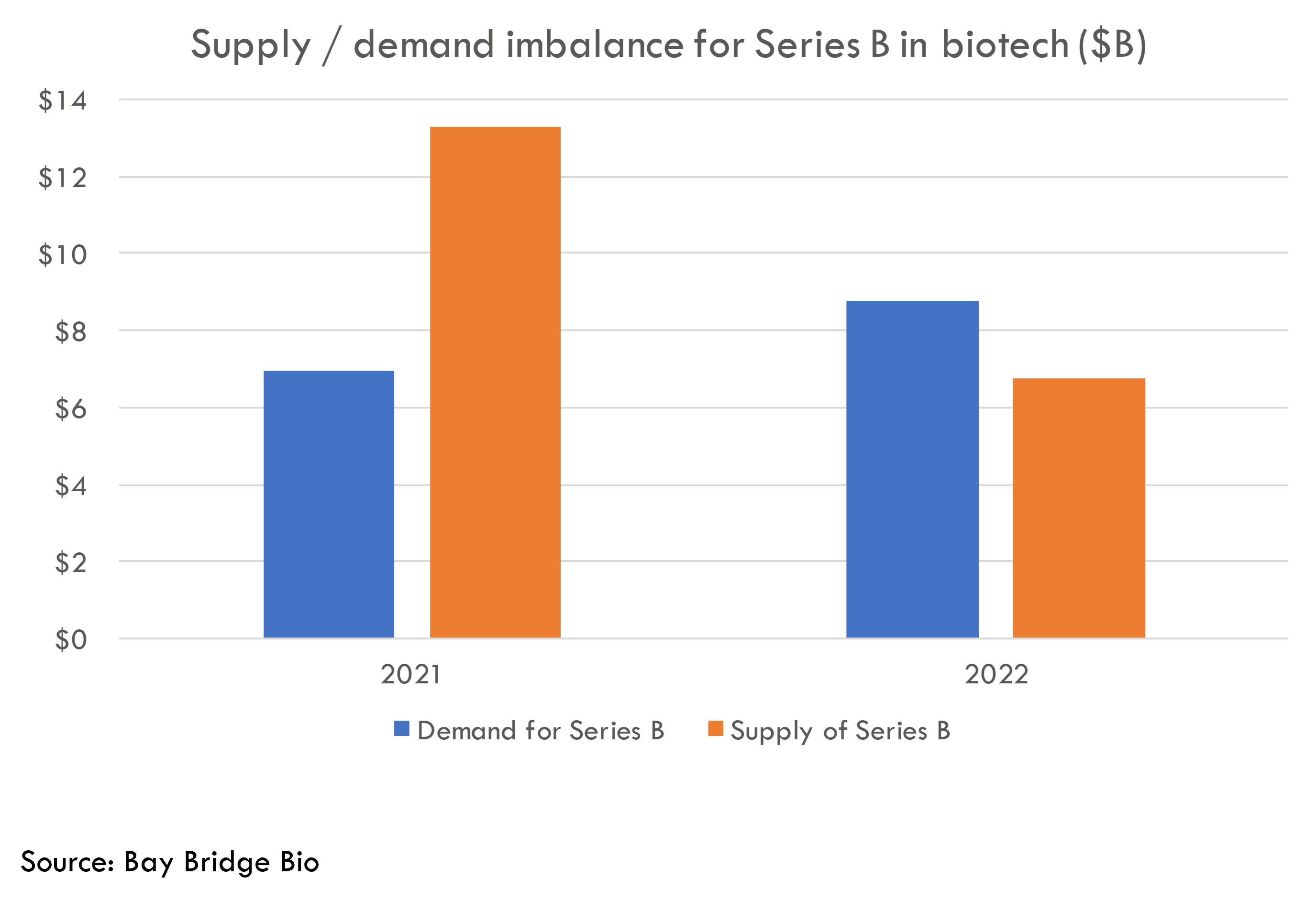

This is because IPOs provide not just liquidity, but also an important source of funding (to the tune of $10B+ in funding per year at the height of the bull market). Crossover investing – investing in the last private rounds before IPO – has also fallen off a cliff after the IPO market crashed. So the supply of capital to private biotech startups has plummeted.

If a sharp drop in supply of capital wasn't bad enough, the demand for private capital has increased. The amount of Series A / seed capital invested in biotech startups has been breaking records nearly every year for the last 5-10 years. There have never been as many startups in need of venture / growth funding, just as the supply of that funding is drying up.

There is roughly an $8B shortfall of follow-on capital for Series A companies now, compared to a year ago. VCs have spent the last year or so figuring out how to make up that shortfall – usually by reserving more capital for supporting select portfolio companies, and slowing the pace of new investments.

The last option for these companies is to partner with big pharma in a non-M&A deal. That can mean selling outright or licensing key assets, doing a discovery or development deal on a platform, raising equity, or a combination of that or other transaction structures. Big pharma is always on the lookout for new science, and startups have a lot to offer potential partners.

Why has the venture market held up?

With all of these challenges, how has the seed and early venture ecosystem remained fairly solid?

The answer is that it takes time for public market disruption to filter down to private companies.

Defensible clinical trial cost estimates

Get transparent cost estimates for any trial in minutes. Input an NCT ID or upload a protocol, then see a full cost analysis report.

Looking back at the start of the funding crisis, we can see how long it takes public market turbulence to propagate upstream.

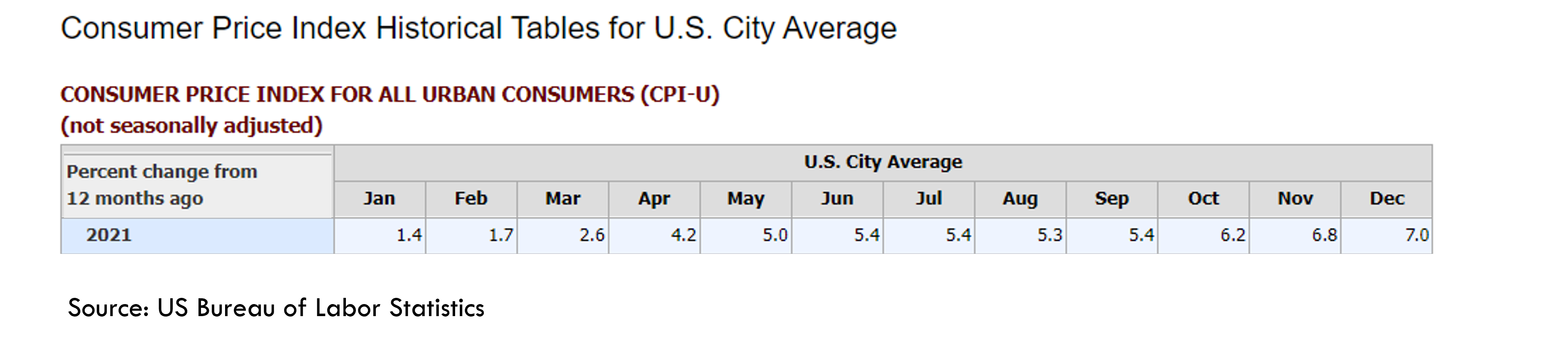

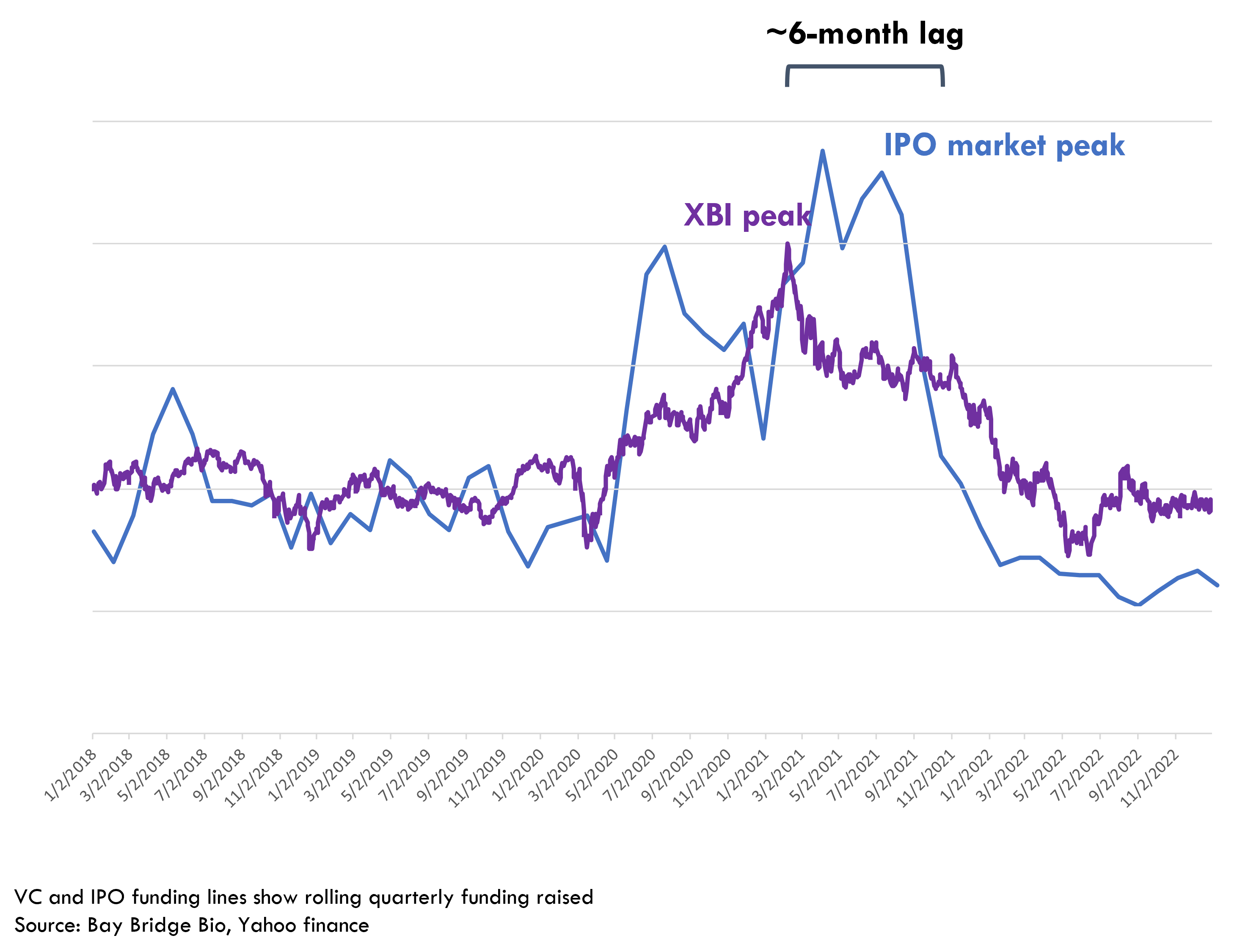

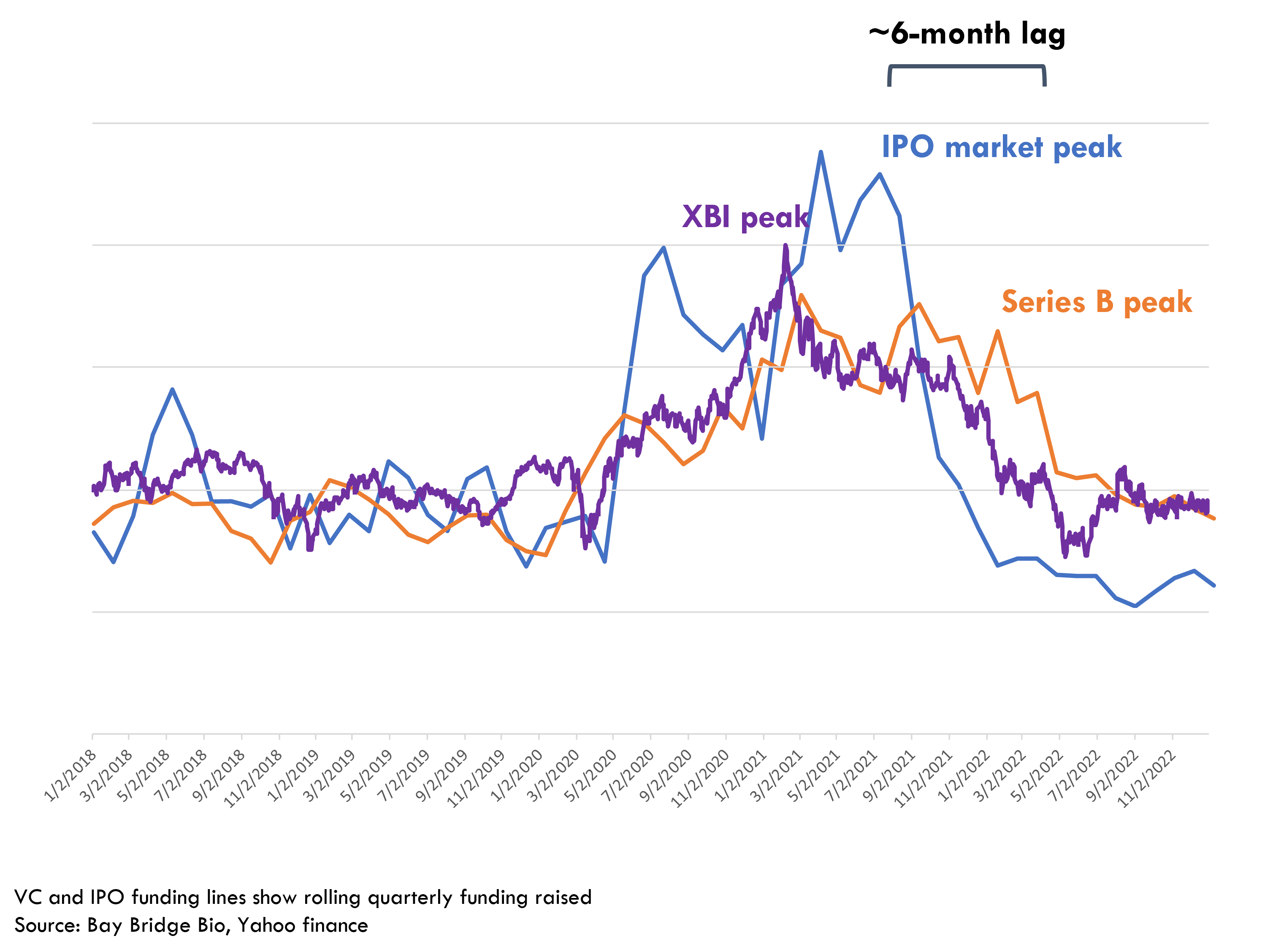

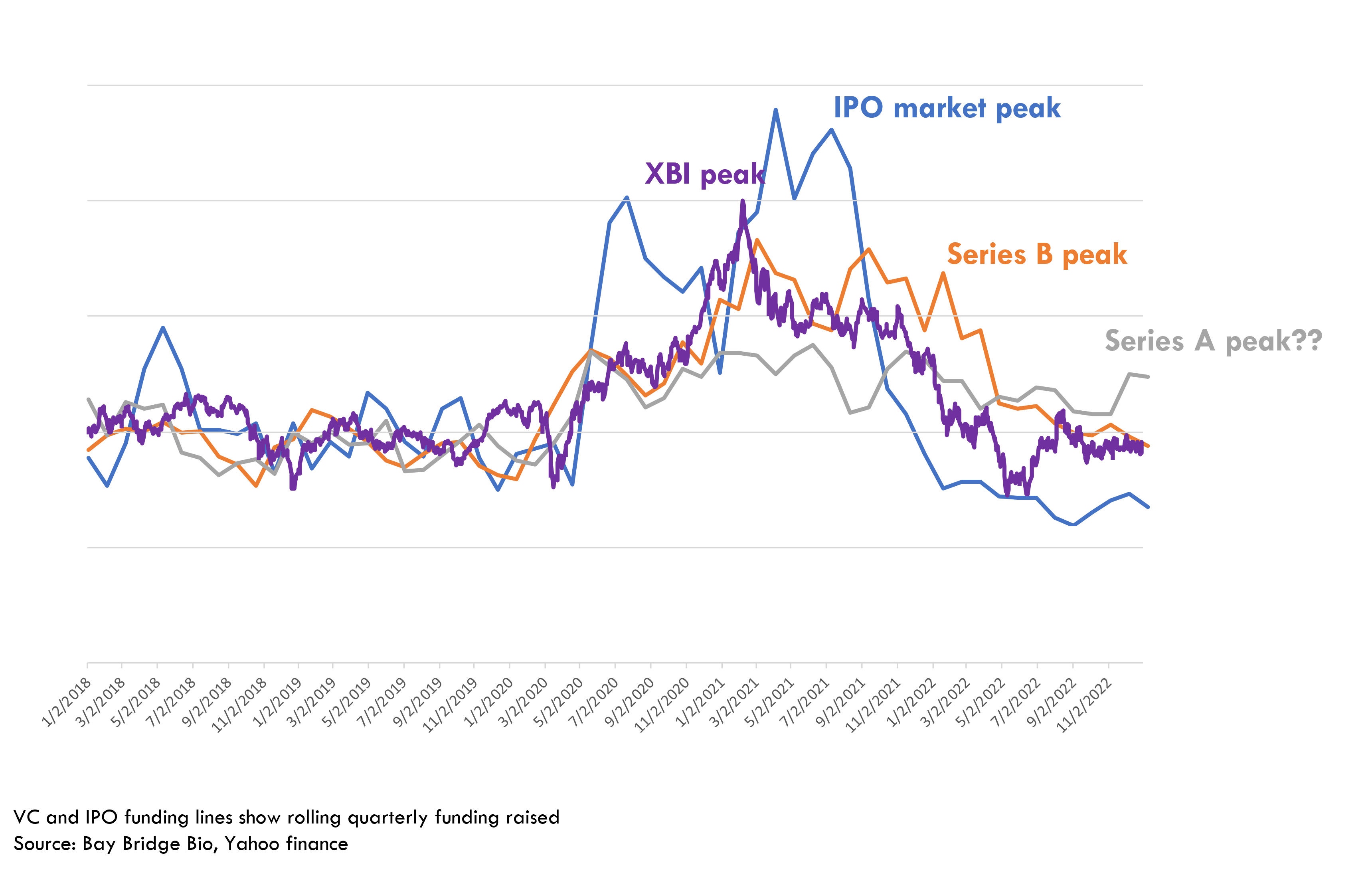

It started in early 2021, when inflation began to pick up. Investors anticipated that the Fed would raise rates in response to rising inflation, which hurts the valuations of growth companies.

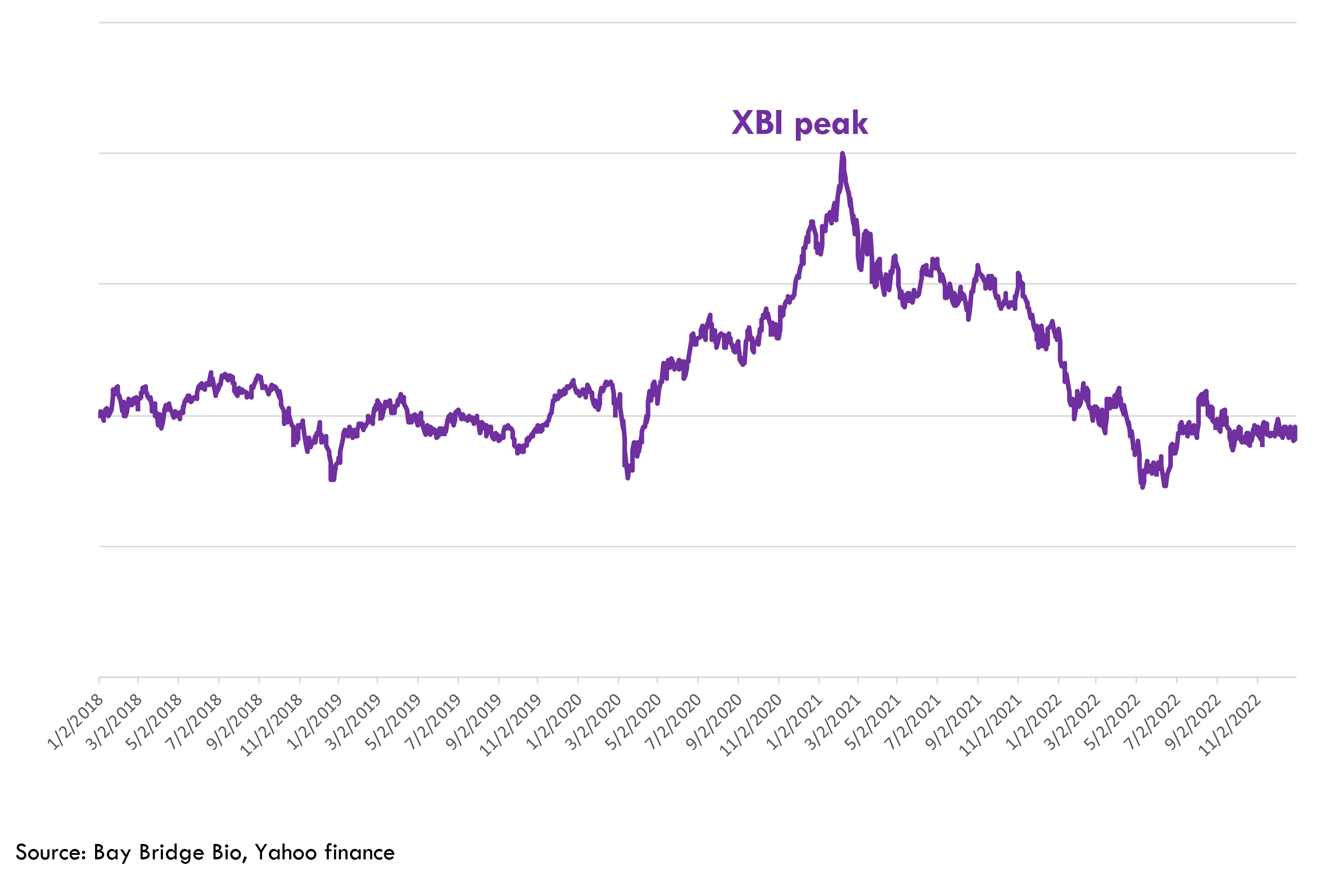

So growth stocks, especially biotech, dropped. The XBI biotech index peaked in February 2021 and is down about 50% from peak.

The IPO market soon followed – if investors are dumping biotech stocks, they aren’t going to want to invest in the riskiest of stocks -- IPOs. After a roughly six-month lag, the public market turbulence led to the IPO market shuttering.

The next domino to fall as Series B, or crossover, investing. Crossover investors fund the last private round before companies go public, and then help the companies go public. So if the IPO market is shut, the crossover trade doesn’t work.

The Series A and early venture market have remained stable, but that domino may be falling. As we have seen for IPO and crossover markets, it takes time for investors to adjust to changes in downstream capital markets. The fear that they may miss out on a rebound makes investors worried about slowing down too early. And the idea that public market turmoil can trickle down to seed and Series A markets can seem too abstract to be real, especially when investors see Seed and Series A deals continuing to close left and right despite talk of pending trouble.

Implications for startups and investors

That isn't to say investors are ignoring looming trouble. Investors have spent the last year or so triaging their portfolio, trying to figure out how much money they’ll need to set aside to protect their portfolio, and how much they’ll invest in new companies. If the market doesn’t recover, VCs will have to make hard decisions about which companies to support. Many investors have already been doing this (in fact, there is evidence that much of the Seed and Series A activity in the last year or so has been driven by emerging VCs that don't have an existing portfolio to support).

The decisions about which companies to support will be driven in part by the VCs’ conviction around individual companies, and in part by what downstream investors and potential acquirors are looking for.

Flight to quality

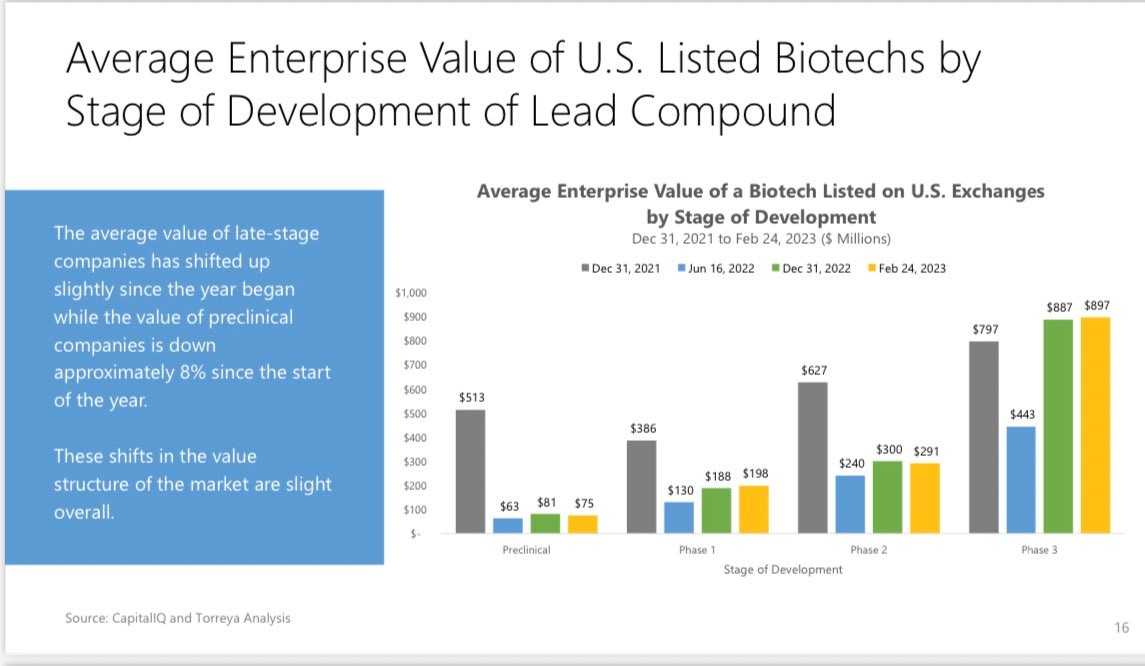

If the public markets are a guide for private investors, the latest trend is a flight to quality. In biopharma, quality is the likelihood of developing a blockbuster drug that provides a huge amount of revenue and clinical benefit.

So, all else equal, Phase 3 companies are higher quality than Phase 1, as there is inherently less risk. Likewise, companies with large markets (in terms of number of patients as well as level of clinical benefit per patient) are higher quality than companies with smaller markets. More differentiated products are higher quality than me-too products.

The way public markets are shaking out is that there is plenty of capital for the highest quality companies, and not much for anyone else.

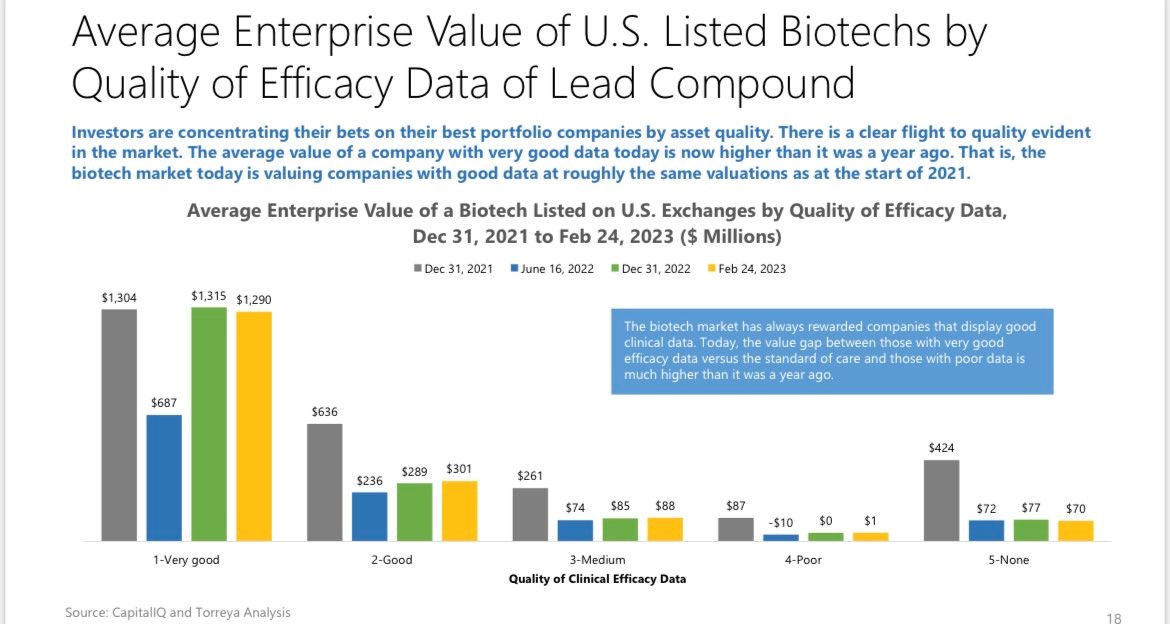

Torreya Partners did a great analysis of this phenomenon. The above chart shows that Phase 3 companies have retained most of their value throughout the crash, while all other companies are getting crushed.

Likewise, companies with very good data have held up, while anything less than that has been punished by investors.

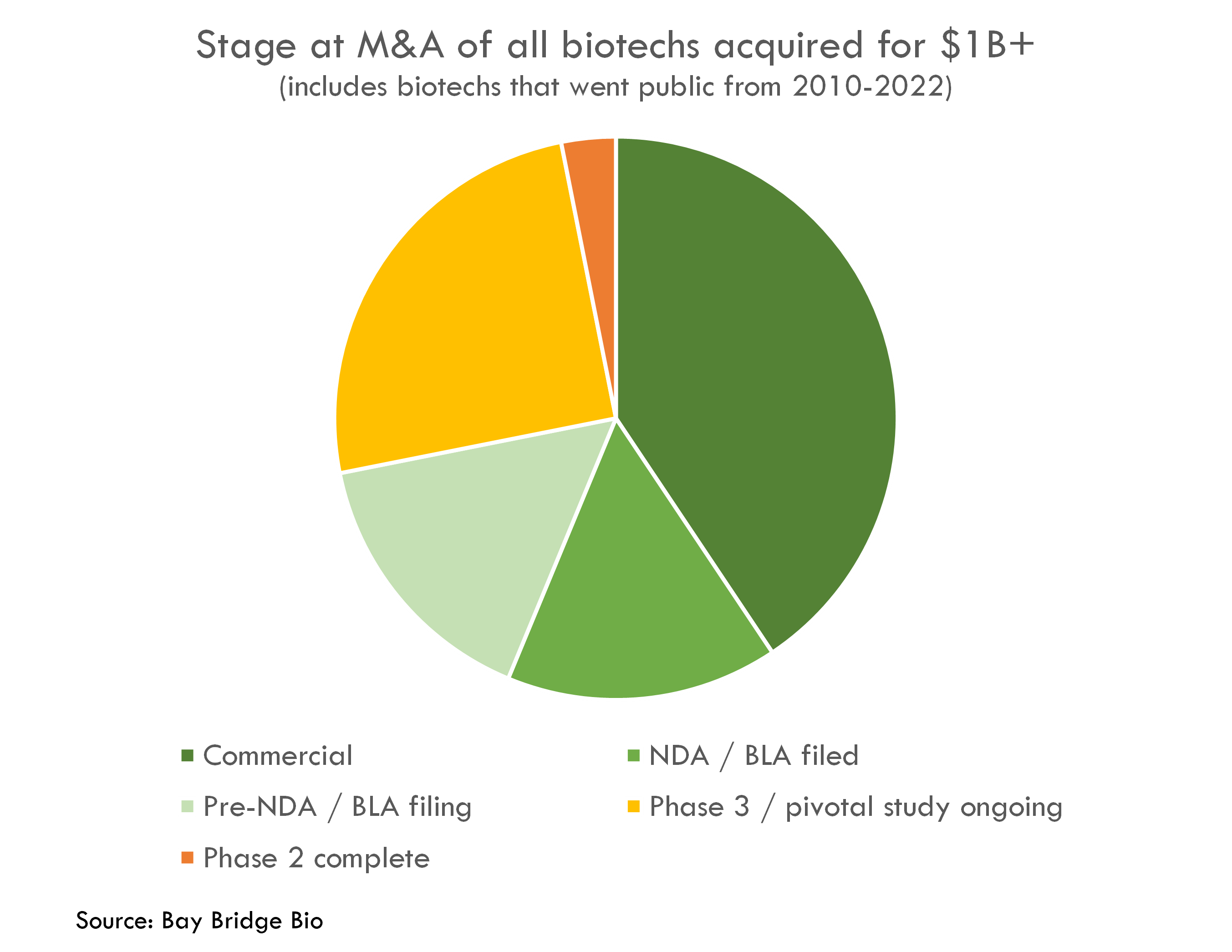

Why this binary dichotomy between quality companies and everyone else? One explanation is that historically, big pharma only pays up to acquire derisked, high quality assets – and will pay almost any price for them. We analyzed all M&A of biotech startups that went public since 2010, and all but one of the $1B+ acquisitions was for companies with a Phase 3 or approved asset. In other words, big pharma only pays big money for high quality assets.

(Since this post was originally published, Prometheus Biosciences was acquired with its lead asset Phase 3 ready for $11B, and Bellus Health, a Phase 3 company, was acquired for $2B.)

So public equity investors are betting that the highest quality companies will get acquired for huge premiums, while other companies will be left to weather the stormy markets on their own.

In a way, the market is shifting from a focus on high-science platform companies all the way back to the conservative build-to-buy strategy of the late 2000s and early 2010s. Capital is scarce, but big pharma companies have a ton of cash and are facing (another) patent cliff. The longer equity markets remain under pressure, the more the biotech VC market will resemble the more challenging ecosystem of the 2000s (one of the few collections of content that documents this period is Bruce Booth's early blog posts; like many "old school" biotech VCs, Bruce seems more sanguine than many other investors about the current funding environment).

For investors, private marks that have not been revisited will gradually be marked to reflect the current market reality. The timing of this will vary from fund to fund, but LPs should be mindful of how their GPs mark their portfolios.

What are startups to do (as most are far from a Phase 3 asset)? The closer you are to having a high quality Phase 3 asset, the better. A combination of streamlining your pipeline, partnering with pharma, and convincing your existing investors that you will be one of the survivors seems the best option.

Any good news?

The market is unlikely to return to the heights of the COVID frenzy, but there are some signs of thawing and increasing risk tolerance amongst equity investors. The long-awaited Fed pivot seems closer than ever as banking turmoil increases the odds of a recession, and speculative activity is returning to markets. However it seems that biotech has not benefited from this increase in risk tolerance, perhaps as investors see other more attractive areas to deploy capital (generally biotech is one of the last markets that generalist investors turn to during the bull phase of an economic cycle).

Pharma does indeed seem willing to pay up for high quality assets, as evidenced by the recent Prometheus and Bellus transactions. Companies that have truly valuable assets still command premium valuations and can attract sufficient capital.

Just as what goes up must come down, what comes down will go back up. Partnering with big pharma companies to weather the storm, while focusing developing only the highest-value internal assets, may be the best way to weather the storm and emerge stronger.