Biotech platforms are out, products are back in

June 20, 2022

Buzzy biotech platforms were a hallmark of the COVID boom.

But these highly valued companies have been hurt the most by the post-COVID crash.

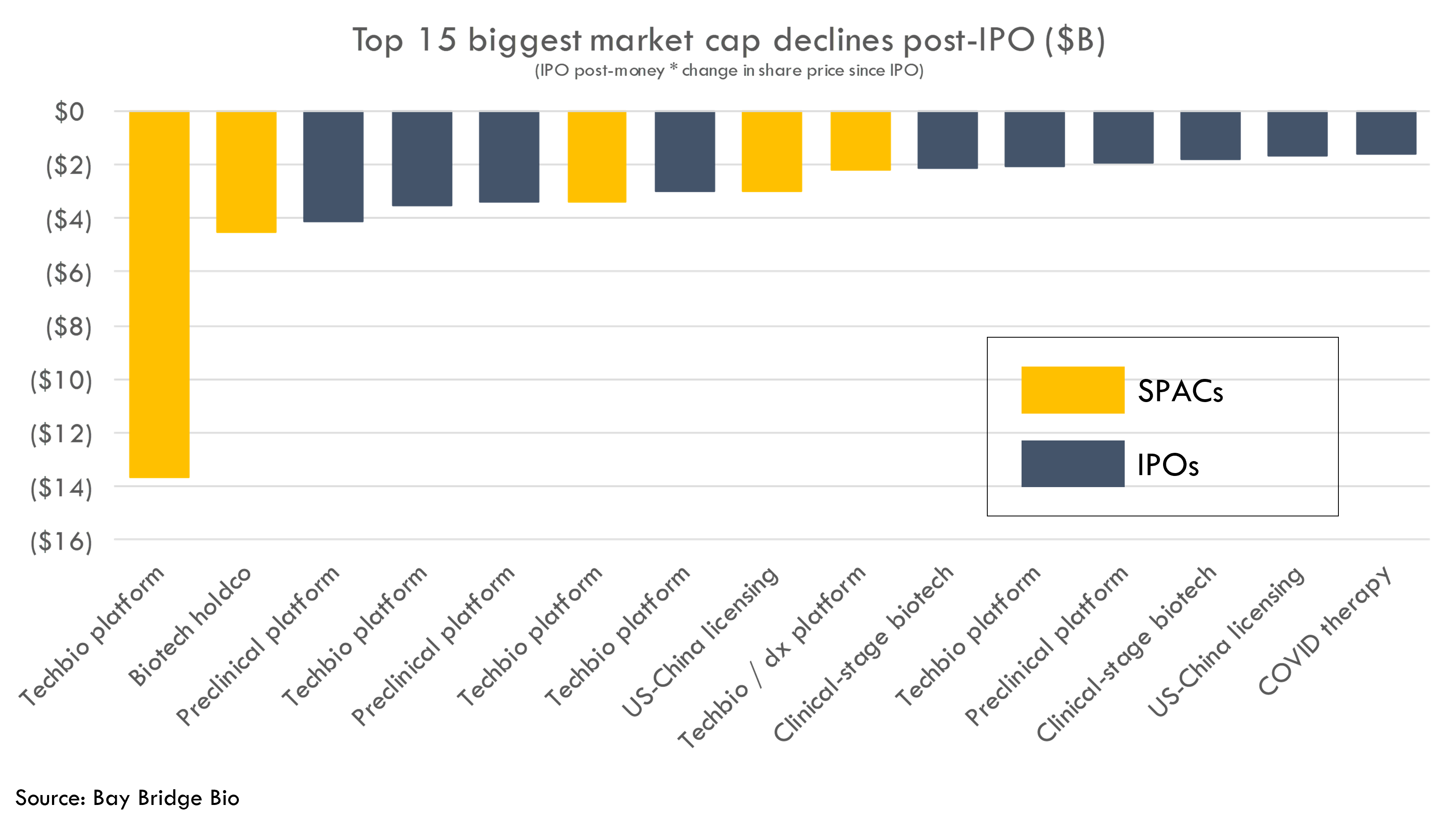

There were 500+ biotech startup IPOs and SPACs since 2010. We analyzed the biggest winners and losers of this group, as measured by IPO valuation multiplied by change in stock price since IPO.

Seven of the top 10 biggest underperformers were platform biotech companies. On the other hand, all of the biggest outperformers had derisked assets (approved products or products in pivotal studies).

SPACs and techbio platforms have been the biggest underperformers: 5 of the 10 biggest losers by market cap were SPACs, and 5 of 10 were tech-bio companies. This is despite SPACs and techbio IPOs representing a tiny fraction of total biotech public market debuts. SPACs represent 5% of total new public market entrances but account for 50% of the 10 worst-performing stocks. Similarly, tech-bio represents 5% of total biopharma public market entrances and represents 50% of the 10 worst-performing stocks by market cap.

For companies, this presents a paradox: platforms have underperformed, but you need a platform to build a lasting company.

How do you resolve this paradox? One solution is to focus on products first, and then build a platform to serve those products.

In the words of Bob Swanson, founding CEO of Genentech:

We were very focused on products, and that made a big difference. I know Cetus at the time was more into developing the technology. I said "Well, let's make a product, and we'll develop the technology we need to make the product, and let the product drive the science, rather than the other way around." Actually, we wound up doing better science because of that, and also we got a product.

- Bob Swanson, founding CEO of Genentech

Value in biotech comes from helping patients

Three fundamental rules of biotech explain why products tend to be more valuable than early-stage platforms, and why platform companies become valuable when they develop good products:

- Value comes from making sick patients healthier. Products -- ie medicines -- make patients healthier. Platforms only help patients indirectly, through the products they generate.

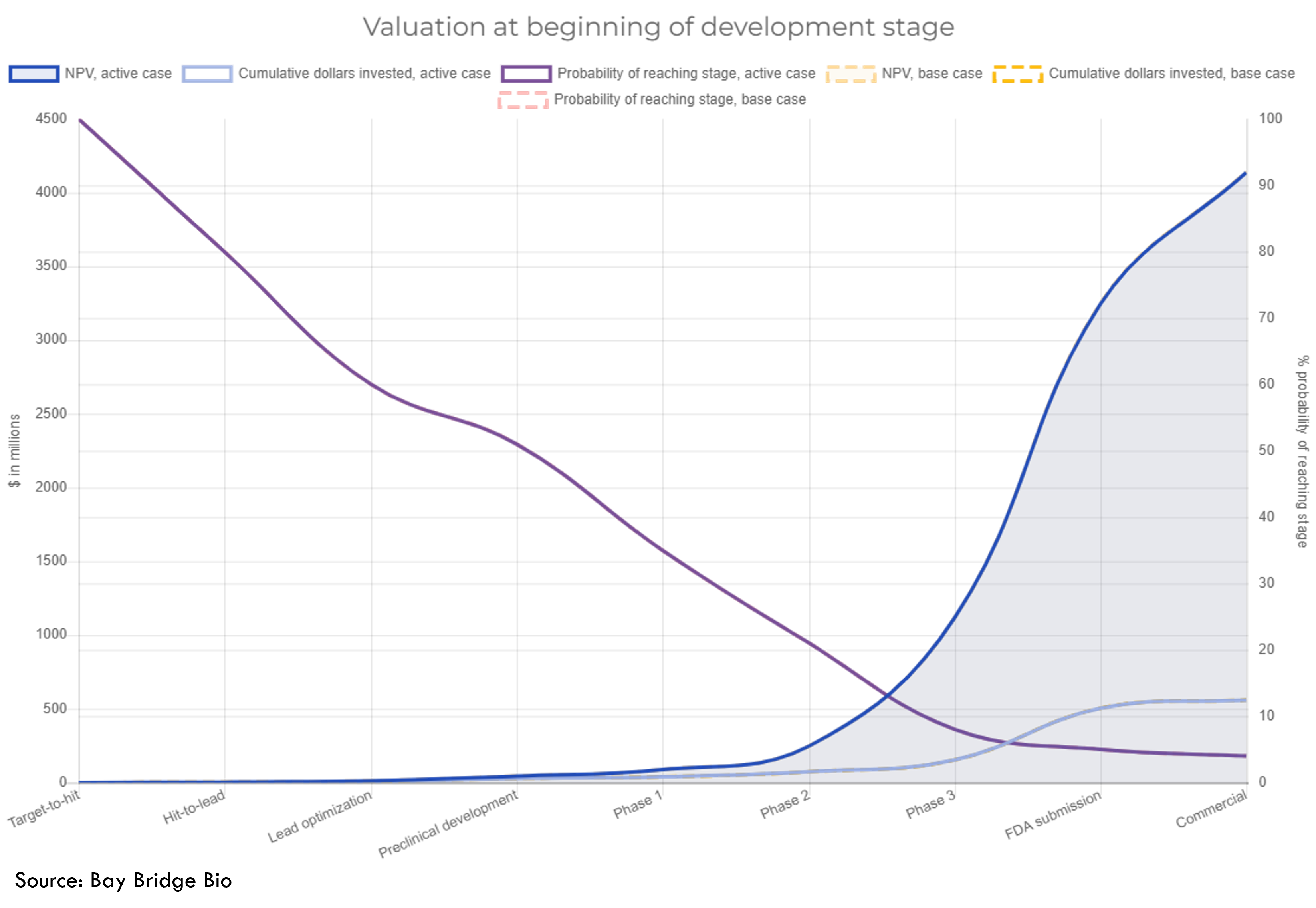

- Drug development is incredibly risky. Value increases exponentially as products advance in clinical development. Hundreds of discovery-stage programs are worth less than one blockbuster approved product.

- Most value accrues to first-in-class or best-in-class products. Hundreds of undifferentiated products are worth less than one first-or-best-in-class product that provides meaningful clinical benefit to patients with severe unmet need.

Our drug valuation calculator illustrates these concepts using data from studies of drug R&D costs:

In short: quality of R&D programs is more important than quantity. Most hits that come out of a screening platform are NPV negative. If quality is low, then the value of a platform decreases with scale. A valuable platform is one that can find a small number of valuable programs, not a large number of mediocre ones.

The easiest way to build DCF models

Build robust biotech valuation models in the browser. Then download a fully built excel model, customized with your inputs.

The market rewards derisked, differentiated products

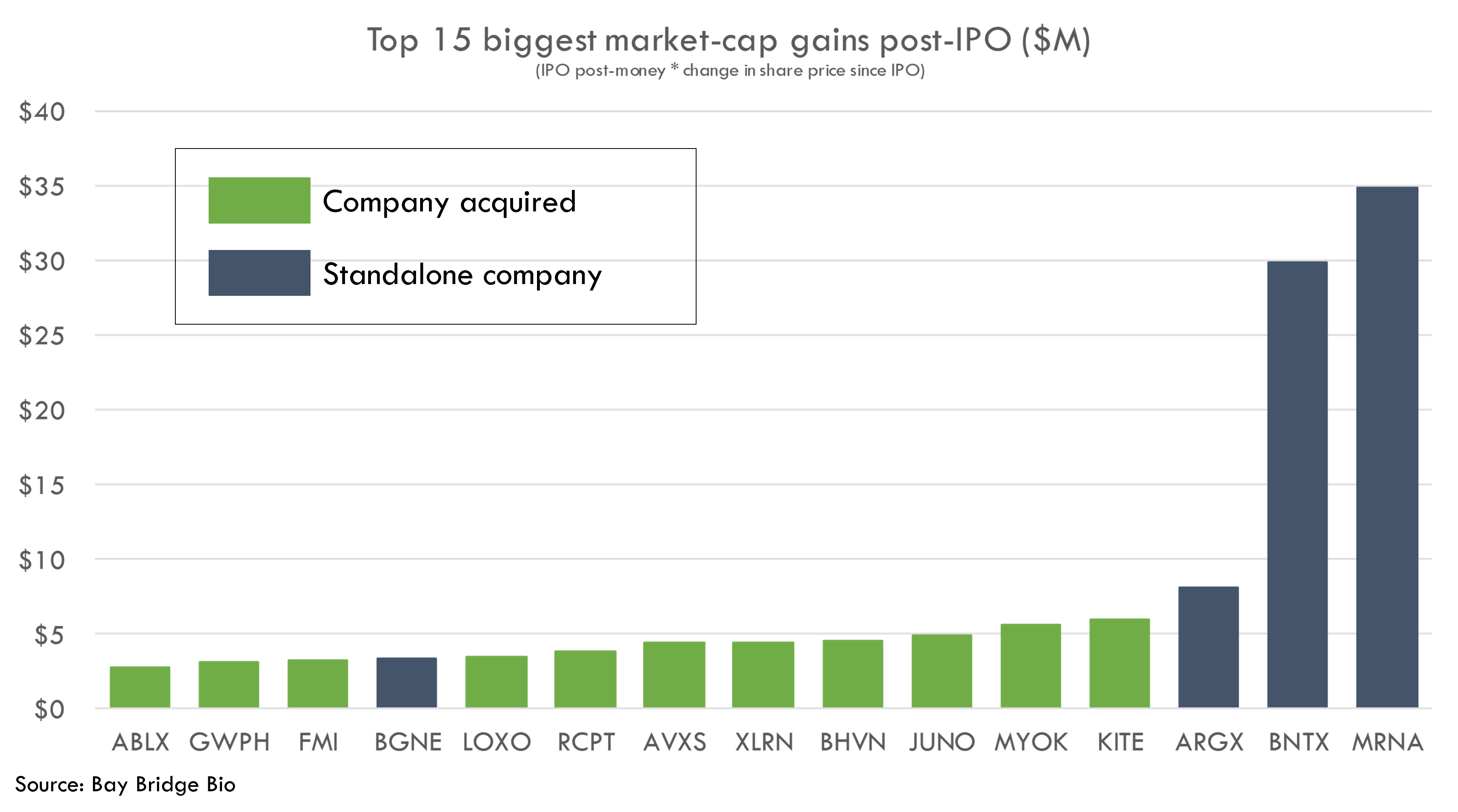

If the chart above is true, we can expect the best-performing stocks to be those with late-stage products.

This is in fact what we see in the IPO performance data. All of the biggest market cap gainers of the 2010-2021 IPO boom have mature and valuable products.

All of these companies have either commercial products, products under review for regulatory approval, or products in pivotal studies.

Many of these companies have platforms in addition to advanced products. But most of their value comes from their assets, not platforms. Arguably, Foundation Medicine was the only one of these companies that was acquired more for platform value than product value.

Even BNTX and MRNA -- the two stocks that stoked the platform biotech frenzy -- only really traded up as they developed their COVID vaccines. Prior to COVID, MRNA was trading below its IPO price.

Every time you see a biotech stock double or triple overnight on good data, you are seeing this principle in action. Good clinical data is the currency of value in biotech. Specifically, good clinical data is data that demonstrates first or best in class potential to provide a meaningful clinical benefit to patients with significant unmet need.

CRISPR 1.0 -- the original preclinical platforms

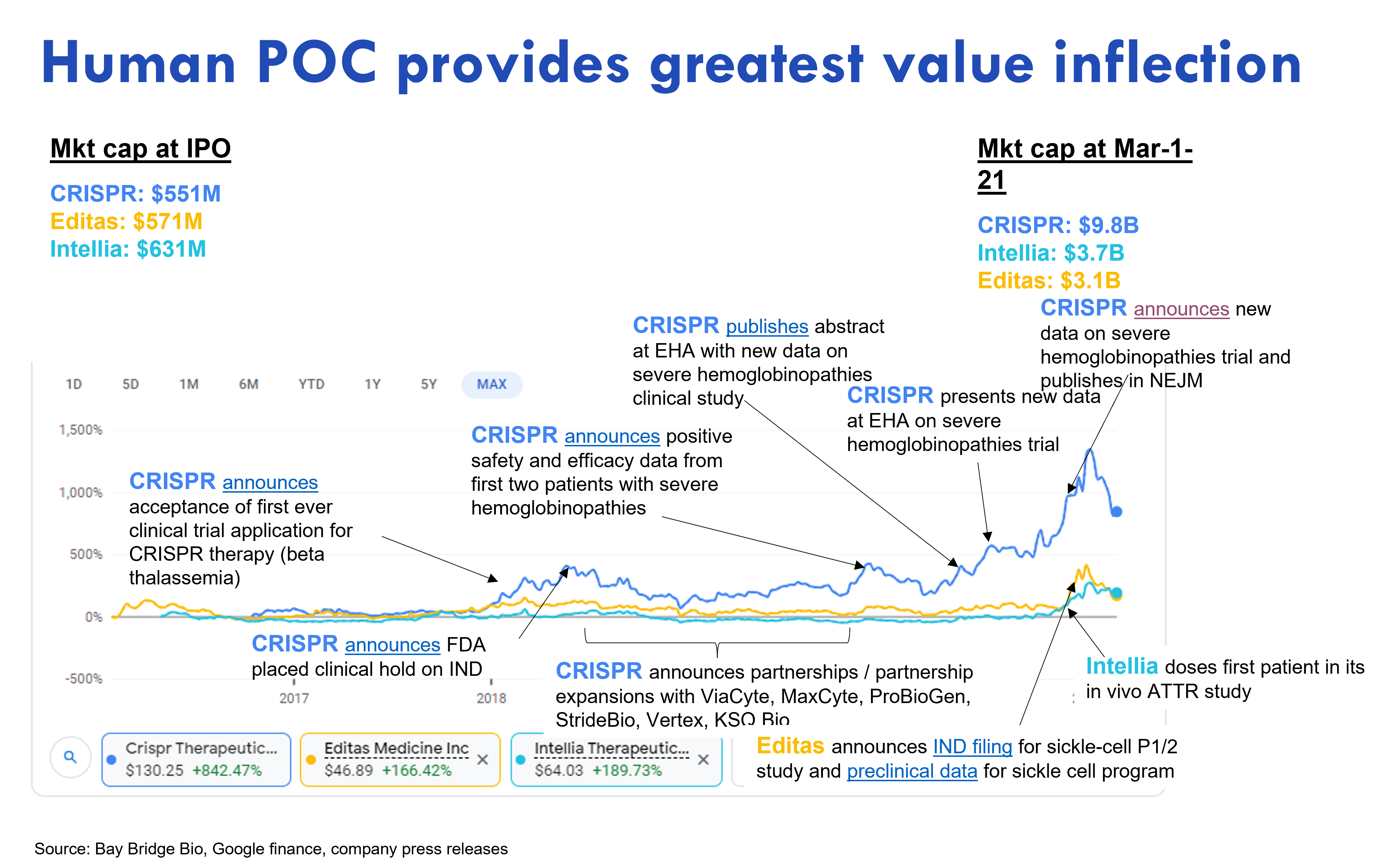

We can look at the original preclinical platform biotech IPOs -- CRISPR pioneers Intellia, Editas and CRISPR Therapeutics, to further demonstrate the link between clinical progress and value creation.

These companies all went public while preclinical at similar post-money valuations of $550-630M. They traded in line until CRISPR Therapeutics moved into the clinic. As CRISPR's clinical study gradually released data showing the drug worked, the market responded by giving the company a higher valuation 1. Intellia and Editas, which were slower to the clinic, only started trading up as they entered the clinic, and later as they released positive data (the above chart is from an analysis we did last year; we didn't update it for this post, but the overall point still holds).

Why did CRISPR's stock go up on clinical data? The data showed CRISPR's product provided a significant clinical benefit (potential cure) to patients with severe unmet need (severe hemoglobinopathies -- sickle cell disease and beta thalassemia) and had first-in-class or best-in-class potential (CRISPR's clinical program was neck-in-neck with bluebird bio's gene therapy study in severe hemoglobinopathies, so potentially first-in-class, and CRISPR had best-in-class potential as it used a non-integrating vector and used different tech -- CRISPR -- to edit genes).

Notably, CRISPR announced several partnerships for its platform. But none of these moved the stock.

Data showing scientific or technological differentiation (as opposed to clinical differentiation) also did not move the stock price. Scientific and technological differentiation only matters to the extent it leads to clinical differentiation -- a better product for patients. A common investing strategy during the COVID bubble was to identify promising technology trends and then invest in companies with the best tech in a trendy area. This strategy misses the important point that products are the mechanism by which new technology realizes its potential.

Just like investors in the dotcom bubble who thought the internet would change the world and lost all their money, biotech investors can be right about the long-term promise of a technology but still get burned. Betting on technology alone without considering company and product fundamentals is a risky strategy that underperforms betting on fundamentals over the long-term.

Pharma only pays up for derisked, valuable products

The data above suggest public equity investors reward products over platforms. We also saw that most of the biggest gainers were acquired. What does big pharma value?

The easiest way to build DCF models

Build robust biotech valuation models in the browser. Then download a fully built excel model, customized with your inputs.

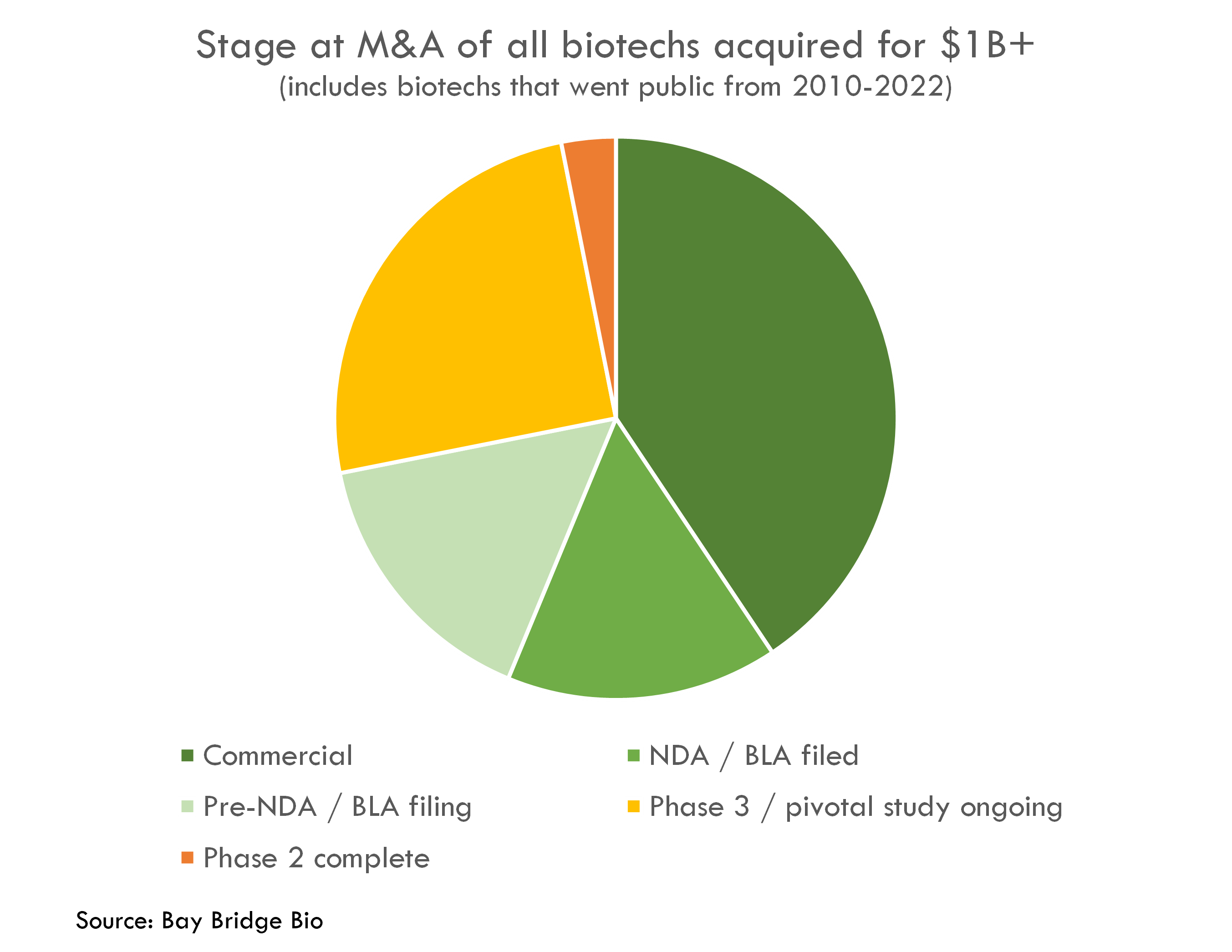

Of the 500+ biotech startups that went public from 2010-2022, 32 were acquired for more than $1B.

All of these had derisked products – 40% had an approved product, 31% had submitted or were about to submit a regulatory filing for approval, and 25% were in pivotal studies.

One (Five Prime) had completed its Phase 2 study and was about to start its Phase 3.

What does this mean for startups?

The excitement around platforms over the last few years is the exception in biotech, not the rule. Over the last 25 years, there have only been a handful of years where pure biotech platforms (those without line-of-sight to a real product) received significant funding: 2020-2021, and also 1999-2000.

Platform risk is the last risk that biotech investors take over the course of a business cycle – and the first risk that they shed when the market turns. Today it is still possible to raise seed or Series A funding around a platform with no line-of-sight to development candidates, but downstream funding markets are more challenging for platforms. Even in 2020-2021, only a handful of techbio platforms made it to the public markets. And the performance of those companies suggests that number won't improve in the near-term.

This creates a paradox: it is hard to fund pure platforms, but you need a platform to build a lasting company. History suggests the way to resolve this paradox is to do what Bob Swanson did when building Genentech -- focus on products, and build a platform to support those products. Don’t focus on the platform for the platform’s sake.

What makes a good product? One with first-in-class or best-in-class potential to provide meaningful clinical benefit to patients with significant unmet clinical need, near-term / derisked path to human proof-of-concept, and strong IP (including composition of matter protection on new chemical entities).

Companies that can develop amazing products with a platform to support them will always thrive in any environment. Genentech was founded in 1976 during the peak of the 1970s stagflationary era. There was no biotech funding market back then -- there wasn't even a biotech industry. If you want to emerge stronger from this environment, there's no better playbook to follow than Genentech's.

The easiest way to build DCF models

Build robust biotech valuation models in the browser. Then download a fully built excel model, customized with your inputs.

1 CRISPR's study was open label, so investigators could see how patients responded to the drug in real time. This enabled the company to publish data gradually as it became available over the course of the study, which is why the stock moved up gradually over time. Most clinical studies are blinded (as opposed to open label), so investigators only see which patients got the drug at the end -- which is why most biotech stocks respond to clinical data with big overnight moves.